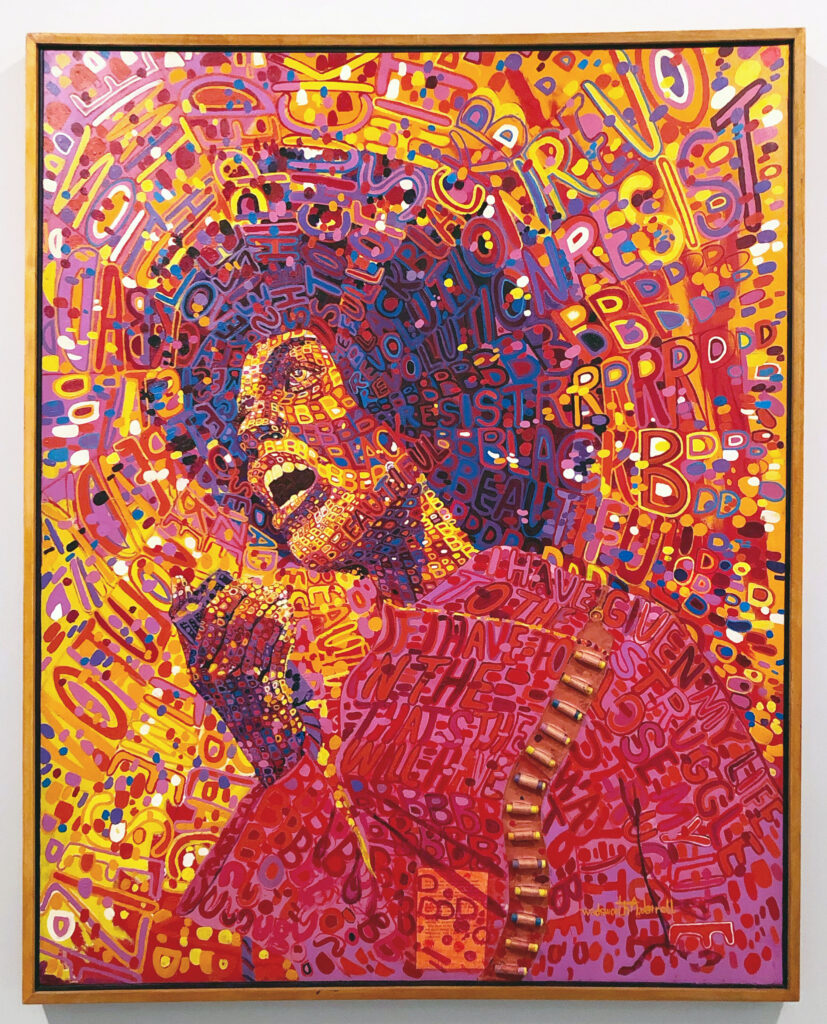

Wadsworth A. Jarrell’s Revolutionary (Angela Davis), 1971, spotted at Brooklyn Museum in 2020, is based off of a photograph of the activist. The colorful painting includes words from her speeches and actual bullet cartridges.

From the museum about the work-

Wadsworth Jarrell’s Revolutionary (Angela Davis) is one of the most recognized paintings associated with the Black Arts Movement, a cultural manifestation of the Black Power Movement. Artists of this movement sought to create uplifting images that called upon Black people to harness their collective power. The power of communal action is here expressed through a chromatic swirl of individual colors that coalesce into a unified image of the radical activist and intellectual Angela Davis. Davis’s militant clothing—complete with bullet cartridges—was modeled after the Revolutionary Suit designed by artist Jae Jarrell, Wadsworth’s wife. An icon of Black Power, Davis continues to lead the prison abolition movement today.

Jarrell, along with his wife, is part of the African American artist collective AFRICOBRA, formed in Chicago in 1968.

Below is part of a statement about the group from their website by another of the founders, Gerald Williams.

AFRICOBRA began very loosely in 1968 as an association of visual artists. We decided to commit our selves to the collective exploration, development, and perpetuation of an approach to image making which would reflect and project the moods, attitudes, and sensibilities of African Americans independent of the technical and aesthetic strictures of Euro-centric modalities. Jeff Donaldson, who spearheaded the movement,Wadsworth Jarrell, Jae Jarrell, Barbara Jones-Hogu, and myself, Gerald Williams opened the lid on what we called AFRICOBRA – African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists. It was an original name that came to identify our place within the broader context of Black art.

Our mission was to encapsulate the quintessential features of African-American consciousness and world view as reflected in real time 1968 terms. For months, beginning as early as 1967, we examined and talked about the forms of expression and images produced by previous generations of artists. We came to the realization that there was not the existence of a consistent, unequivocal, uniquely Black aesthetic in visual arts as there was in other disciplines, notably music and dance. Many of our contemporary artists, at the time, generally said that they “were artists who happened to be black”, or held the view that their work was expressing universal ideas or concepts that were not tied to such a narrow category as Black art. The notion of an intrinsically Black view point, expressed in characteristically “Black ways” was a relatively alien idea for the most part. That notion begged the question as to whether it was possible to create a style or approach to art that at its core could be identified as African-American or Black, notwithstanding the presence of Black imagery or subject matter. If imagery and subject matter were the sole criteria then the question was moot. One could conclude, thereby, that Winslow Homer or any number of artists produced Black art when they painted Black images. After numerous brain storming sessions where such topics were discussed, after test projects and critiques, the five of us mapped out the core principles that became the foundation of AFRICOBRA.