Julia Schenkelberg, “Blue Ocean”, 2020, Blue dye, resin, rusted metal from Detroit factory floors, plaster chips, vintage china, glass from Brooklyn beaches

Malone University Art Gallery’s exhibition Healing Spaces features work by Northeastern Ohio artists Julie Schenkelberg, Chen Peng, Yiyun Chen, and Emily Bartolone. Although the mediums differ, the work flows together in the room. Below are some selections and more about each artist from the gallery’s documentation.

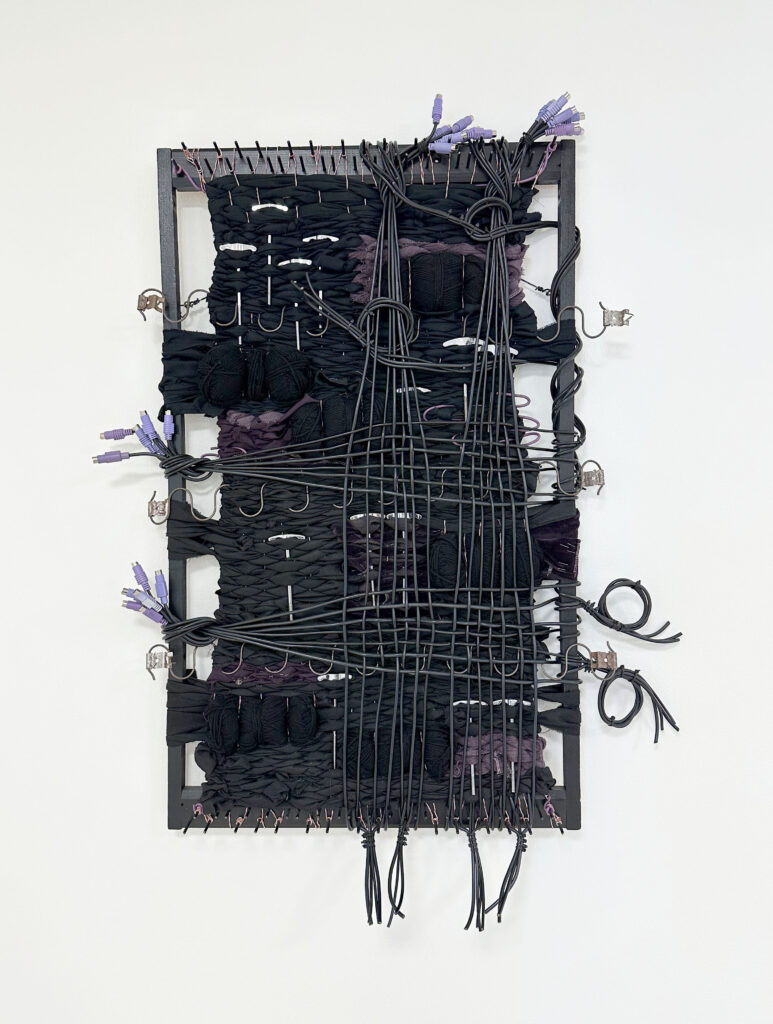

Julie Schenkelberg, “Modern Memorial”, 2020, Found screen, plaster, acrylic paint, vintage leather and fabric, jewelry box interior, glass gathered from Cleveland and Detroit auto and steel factory abandoned floors, vintage glass slide of the Parthenon Frieze

Julie Schenkelberg grew up in the post-industrial landscape of Cleveland, Ohio. Her mixed-media installations start with furniture, dishware, textiles, and marble, combined with concrete, resin, and construction materials, to transform notions of domesticity, and engage with the American Rust Belt’s legacy of abandonment and decay. Using the home as a playground for formal and conceptual subversions, the work aggressively disrupts cohesion within the physical sphere. Familiar furnishings rekindle memories or premonitions of collapse, suggesting both the utter destruction of war, calamities, or urban decay, but also the uncanny juxtapositions of fragile substances such as cloth and china, with industrial materials such as rusty metal, heavy concrete, and tool-made marks such as drilled holes and chain-sawed indentations.

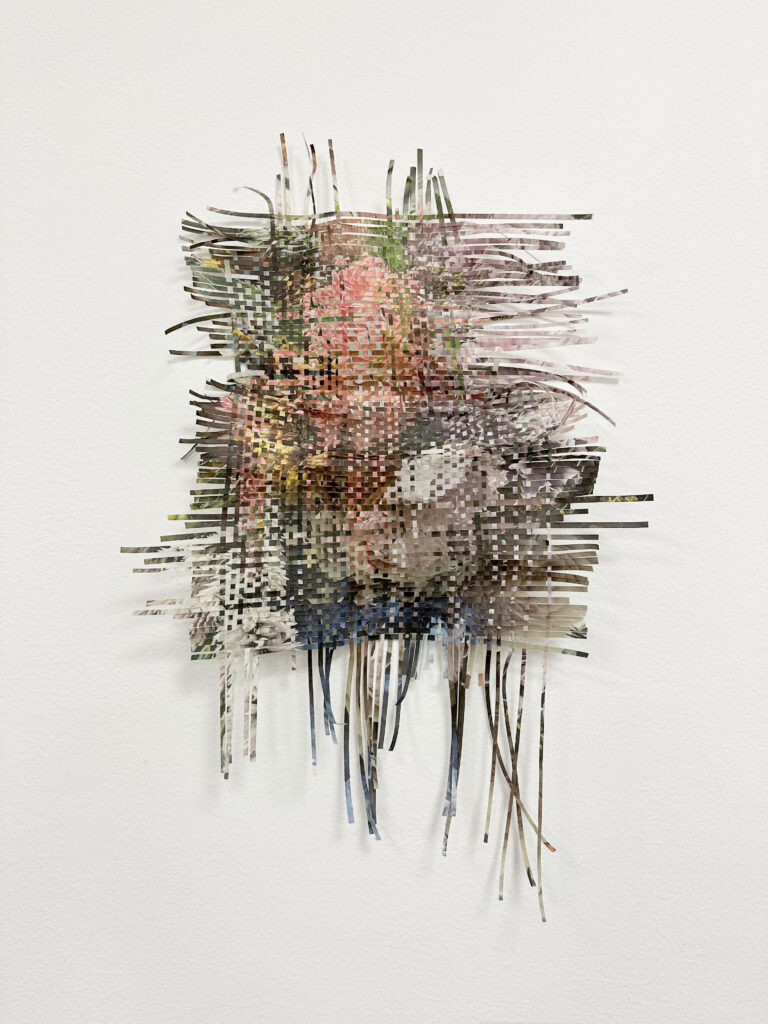

Chen Peng, Paintings from the “Mountains at Night” series, 2023, gouache, acrylic, and oil on canvas

Deriving from a desire to find stillness and grounding as an immigrant, Chen Peng explores the connection between landscape and the complexities of identity and belonging. She creates foreign landscapes from a combination of past experiences, memories, and imagination, delving into the disorienting sense of not knowing where home is. The moon, particularly in its fullness, becomes a symbol encapsulating emotions and metaphors associated with loneliness, reverence, and even terror. Her ceramic pieces extend this exploration of landscapes, featuring textures and marks that convey the essence of mountains, clouds, and the moon.

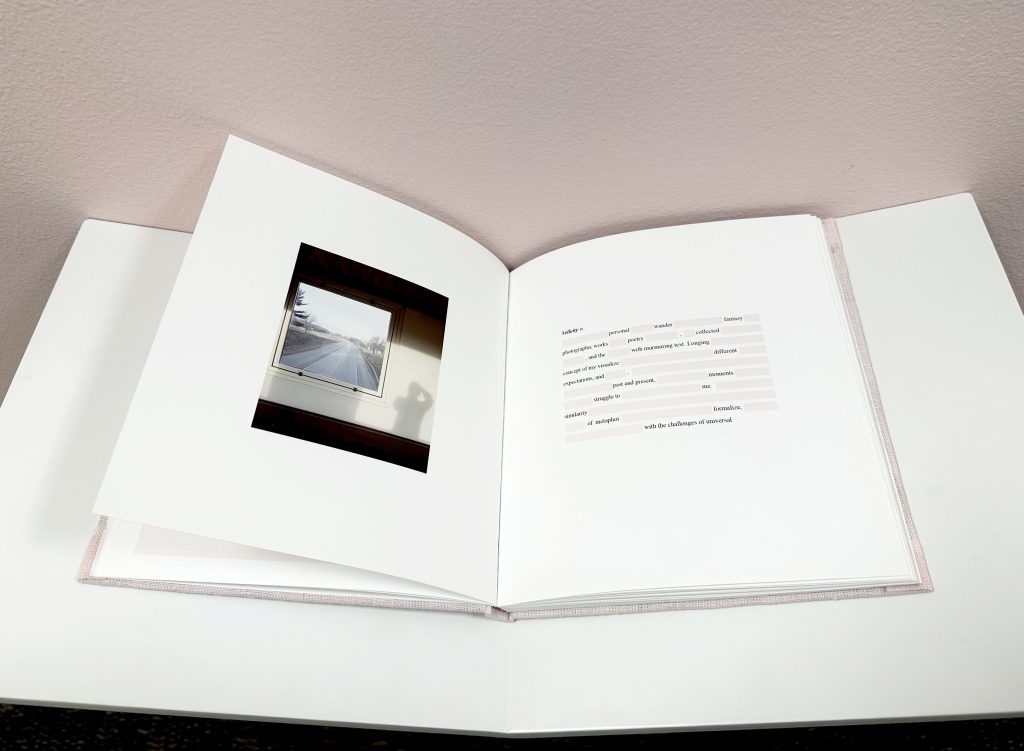

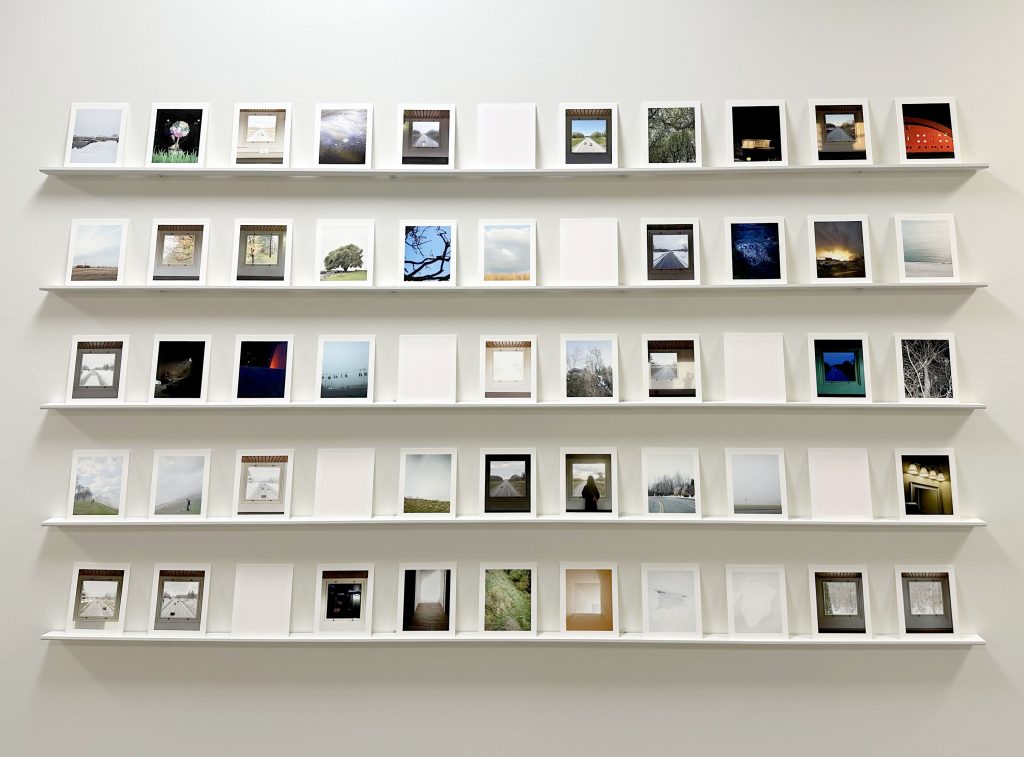

Photographs from from Yiyun Chen’s series “Velleity”, 2016-2018

Yiyun Chen, “Velleity”, detail

The photography of Yiyun Chen is about the process of self-reflection and self-discovery as an Asian immigrant, exploring the relationship between people, environment and society, turning its personal experience and empathy into gentle conversations between humans and nature, capturing the poetic and distance of the environment around us. Through photography, we can take the essence of life seriously again and treat the people and things around us tenderly. Through his lens, they often have similar structure, people look tiny in nature scenes, creating an intimate visual experience. Most of his photographs are captured outdoors, with soft light and harmonious colors often used.

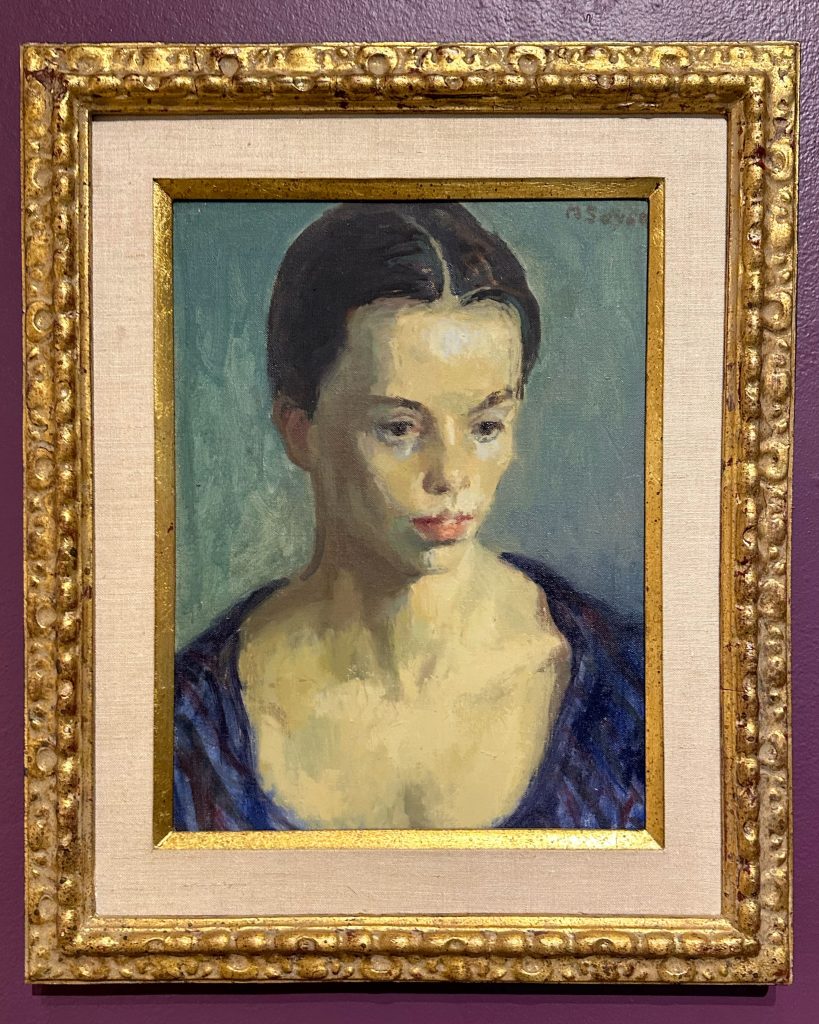

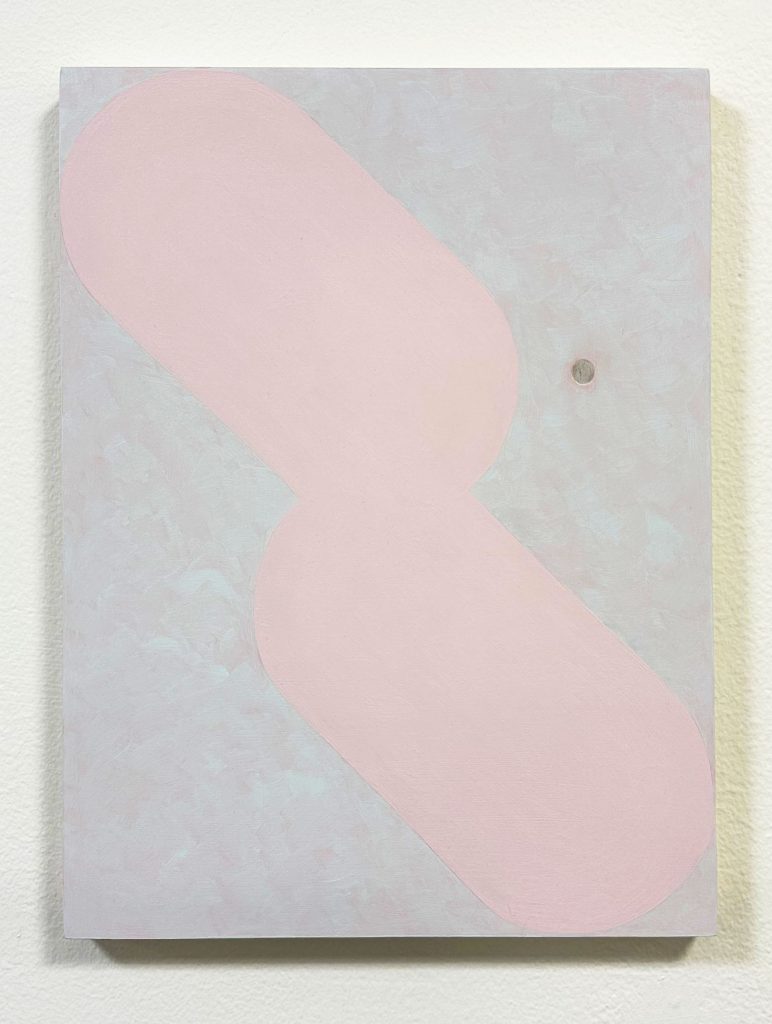

Painting by Emily Bartolone

Painting by Emily Bartolone

Stemming from her infatuation with the formal elements of painting, the work of Emily Bartolone pairs down simple, anthropomorphized shapes in an effort to explore paint and color theory while simultaneously creating tension and humor through color, edges, and texture. The playful, human qualities of painting are incorporated into the work through the use of amorphous shapes animated within the picture plane. Further informed by ideas of the mundane, the awkward, and the jovial that surround everyday life, the complexity of human relationships are mimicked by the shapes interacting on each painting’s surface. In acknowledging that life is not always cordial, moments of tension are placed within the satisfying surfaces in the form of an abrupt mark, a disparate color, or a shift in scale. These ideas are used to take viewers outside of themselves for a short period of time, hoping to offer a break from the bombardment of distractions, notifications, and news we encounter so often on a daily basis.

This exhibition closes 4/9/24.