Barthélémy Toguo (Cameroonian, b. 1967), “Road to Exile”, 2018. Wooden boat, cloth bundles, glass bottles, and plastic containers

Currently on view at Tampa Museum of Art is Time for Change: Art and Social Unrest in the Jorge M. Pérez Collection. The exhibition highlights art from around the world that focuses on social issues.

From the museum-

“It is enough for the poet to be the bad conscience of his age”, stated Saint-John Perse in his 1960 Nobel Prize acceptance speech. Something similar could be said when artists address the transformations of society. We should not ask for measurable political action when their role is to point out, to render evident, to shake us from indifference. Art may not provide answers, but most of the time it interrogates and proposes uncomfortable issues, almost like rubbing salt in a wound. Artists are seldom celebratory, nor do they usually provide solutions-art’s potency lays in the symbolic efficacy of the actions it proposes more than in the practical effects they entail. Paraphrasing Brazilian poet Ferreira Gullar, “art exists because life is not enough.”

Time for Change is structured around six themes or nuclei: Entangled Histories, Extraction and Flows, Artivism, State Terror, Spatial Politics, and Emancipatory Calls. The sections are organically linked and establish dialogue and correlations among artworks that do not necessarily illustrate an argument nor are they contained by one. Entangled Histories proposes essential questions: how do we remember as a society? Who is forgotten by History, and for what reasons? Extraction and Flows examines displacement of peoples (usually forced), as well as the unequal logic on the territory. Artivism: Art in the Social Sphere focuses on political unrest and public protest on the streets. State Terror signals how protest is countered with repression and violence. The fifth section, Spatial Politics, reflects on modern architecture and its role in creating segregated communities. Lastly, Emancipatory Calls summons to reclaim difference, in the understanding that a more just society can only be built on respect for one’s right to be different.

A comprehensive look at the Jorge M. Pérez Collection reveals a tendency towards art with an interest in social change- art that examines the conflicts and contradictions of contemporary society, art that critically analyzes historical events and reframes them in the present. Many of the 60 works on view, due to their size or complexity have rarely been exhibited and are shown together for the first time in Time for Change.

About the main work pictured above, Barthélémy Toguo’s Road to Exile, from the museum–

In 2018, the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill, New York hosted Barthélémy Toguo’s first solo exhibition in the United States. While on site at the Parrish he made Road to Exile, a large-scale installation highlighting the plight of refugees, in particular African migrants in search of a better and safer quality of life. The installation features a life-sized wooden boat that rests on glass bottles. A metaphor of the dangerous voyage across the sea, the bottles represent the fragile line between life and death. The boat nearly overflows with bundles wrapped in brightly colored African textiles and serve as stand-ins for the body. In Road to Exile Toguo employs imagery of the boat as a means of escape rather than a vessel for exploration or adventure.

Below are images from the exhibition as well as some information on a few of the works.

Rashid Johnson, “A Place for Black Moses, (2010), bottom right sculpture, and Christopher Myers “How to Name a Famine, a Fire, a Flood”, 2019, left wall piece

Christopher Myers “How to Name a Famine, a Fire, a Flood”, 2019, Applique fabric

From the museum about the above work-

Storytelling anchors Christopher Myers’ artistic practice. Working in a range of media, he mines history and creates art that links the past to the present. Myers’ tapestries, such as How to Name a Famine, a Fire, a Flood draws on the rich tradition of quilt making as a quiet yet radical form of resistance and protest. The stories depicted center on the effects of globalization on individuals and more specifically, communities of color. In How to Name a Famine, a Fire, a Flood, Myers portrays three different natural disasters linked to climate change. With vivid color and patterned fabric, he illustrates the impact and devastation of these catastrophic events in neighborhoods with minority populations.

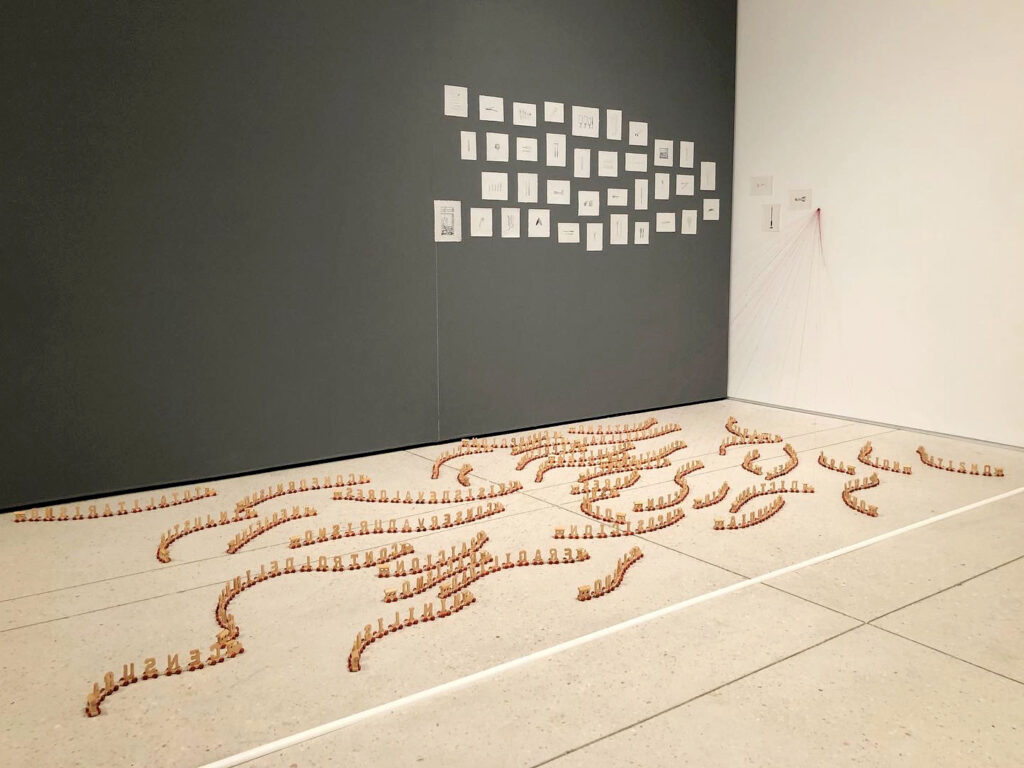

Carlos Garaicoa “La habitacion de mi negatividad (The Room of My Negativity)”, 2003, 39 ink and pencil drawings on rice paper and toy train installation

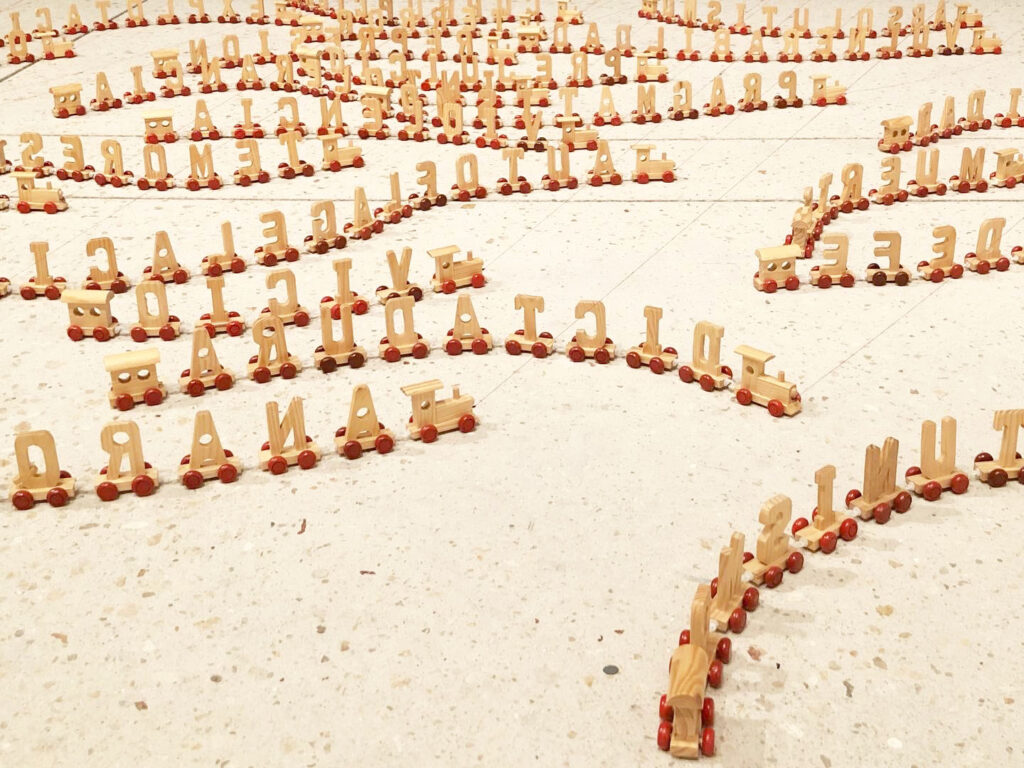

Carlos Garaicoa “La habitacion de mi negatividad (The Room of My Negativity)”, 2003 (detail)

Carlos Garaicoa “La habitacion de mi negatividad (The Room of My Negativity)”, 2003 (detail)

About the above work from the museum-

Carlos Garaicoa works in a variety of media, ranging from installation, photography, and video to performance and public interventions. His early work in the 1990s focused on the urban decay of Havana as result of its political climate and economic strife. La habitacion de mi negatividad (The Room of My Negativity), turns Garaicoa’s lens inward. In this installation, comprised of toy trains and drawings of medical instruments, the artist explores his psyche and subconscious. The train’s engine pulls words that represent Garaicoa’s negative thoughts. Each train is connected to thin red thread that acts as a vein or conduit for the negative thoughts to travel. Arrange in a curved form, the train shapes mimic brain waves or the slink of a snake. Garacoia’s drawings of medical tools serve as mechanisms in which the negatively could be excavated from one’s mind.

Esterio Segura, “La historia se muerde la cola (History Bites its Tail)”, 2015, (statue bottom left); Anamaría Devis, “Infinito (Infinite)”, 2018(upper right)

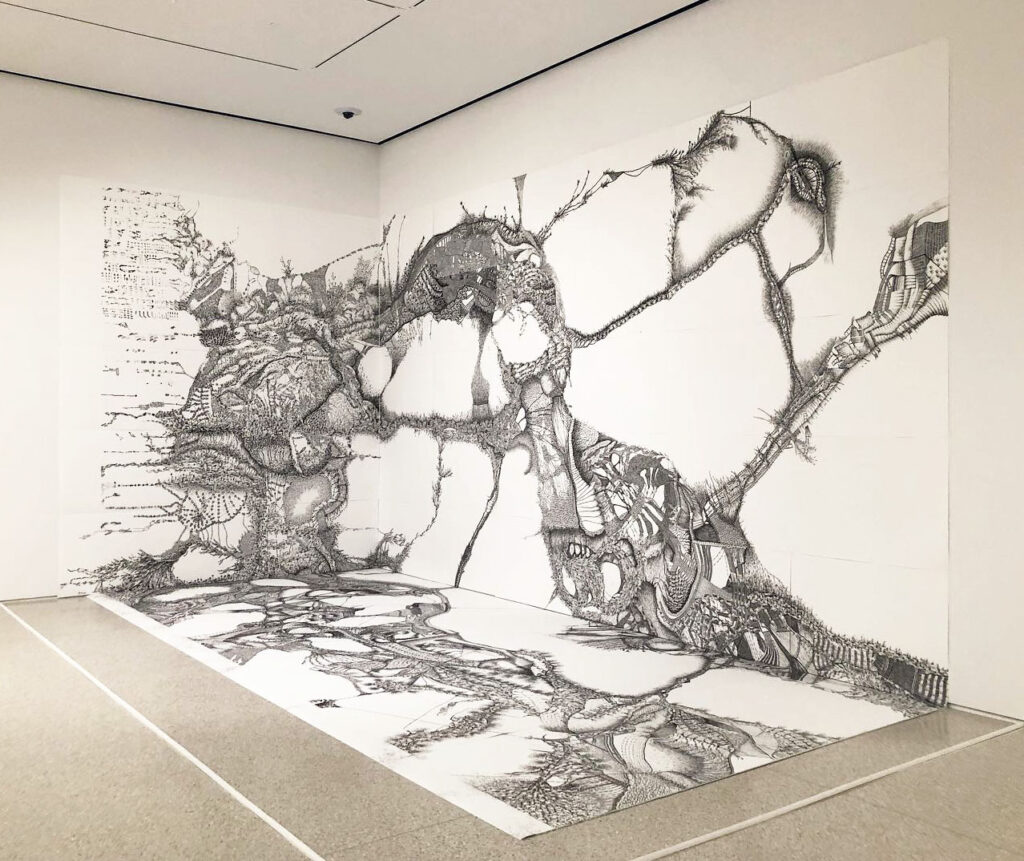

Anamaría Devis, “Infinito (Infinite)”, 2018, Ink on paper

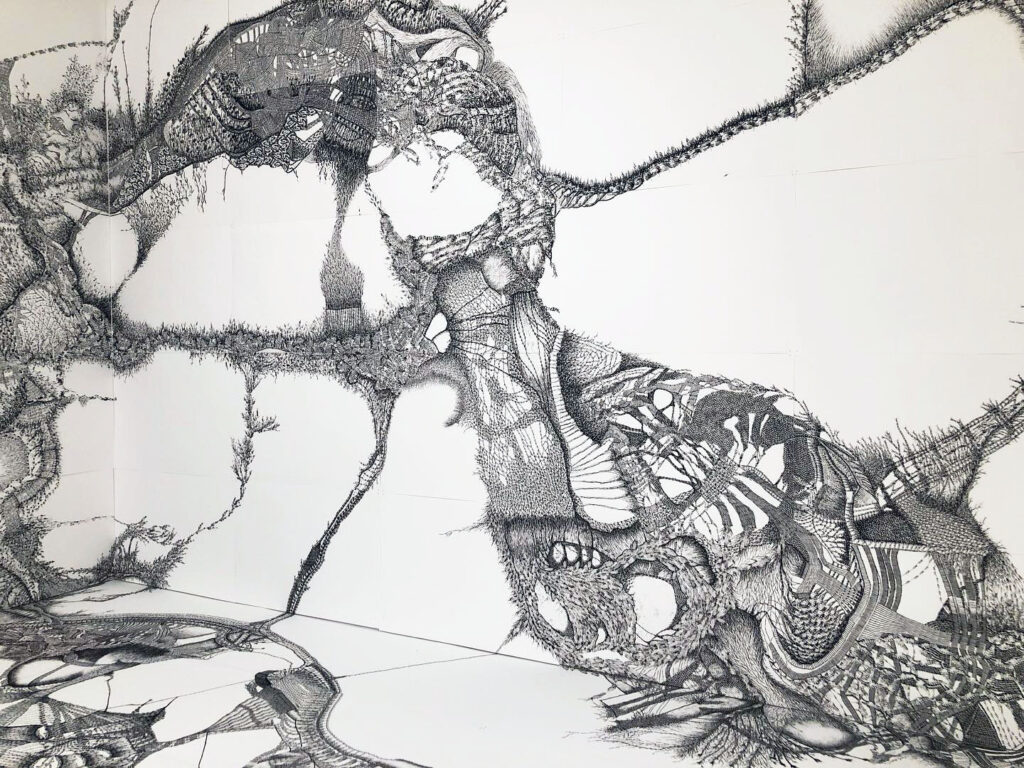

Anamaría Devis, “Infinito (Infinite)”, 2018, Ink on paper (detail)

About this work from the museum-

Anamaría Devis’ large-scale installation Infinito (Infinite) represents the artist’s study of African history in San Basilio de Palenque, Colombia. Escaped slaves founded Palenque and it was the first free town in the Americas during colonial times. While researching this history, Devis discovered that in this region of Colombia, braided hairstyles worn by Africans served as escape maps. Braid patterns reflected safe points in the area’s topography. This silent form of resistance inspired her to look at other bodily topographies like the characteristics of fingerprints, which also had names associated with cartography such as crossing, island, and fork. Devis then began to create drawings that incorporated footprints, braid patterns, and elements of nature. From the drawings she made stamps and each panel of paper that comprises Infinito (Infinite) is rendered from Devis’ various imprints. The result is an abstract representation of the body and landscape visualized through mapping and codes.

Jonathas de Andrade, “A batalha de todo dia de Dona Luzia, de Tejucupapo (The daily battle of Dona Luzia, from Tejucupapo)”, 2022 Images printed on raw falconboard

About this work from the museum-

Jonathas de Andrade collaborated with the Brazilian theater company Teatro Heroínas de Tejucupapo to create a visual reenactment of the historic 1646 Battle of Tejucupapo. For nearly 25 years, between 1630 and 1654, the Dutch occupied the northeast of Brazil including Tejucupapo, a small community in the city of Goiana. During the Battle of Tejucupapo, a brigade of black and indigenous women forced Dutch soldiers to retreat by arming themselves with household and farm objects. The Teatro Heroínas de Teiucupapo commemorates this female-led rebellion each April by restaging the battle with local actors.

Artist Jonathas de Andrade celebrates the power and courage of Tejucupapo’s women with his large-scale photographic installation A batalha do todo dia de Tejucupapo (The Battle of Tejucupapo). The work on this wall, A batalha de todo dia de Dona Luzia, de Tejucupapo (The daily battle of Dona Luzia, from Tejucupapo), presents everyday objects from the home of one of the women participating in Teatro Heroínas de Tejucupapo. This inventory explores the daily struggles, as well as strength, of Brazil’s black and indigenous women that have spanned centuries.

This exhibition will close on Sunday, 8/27/23.