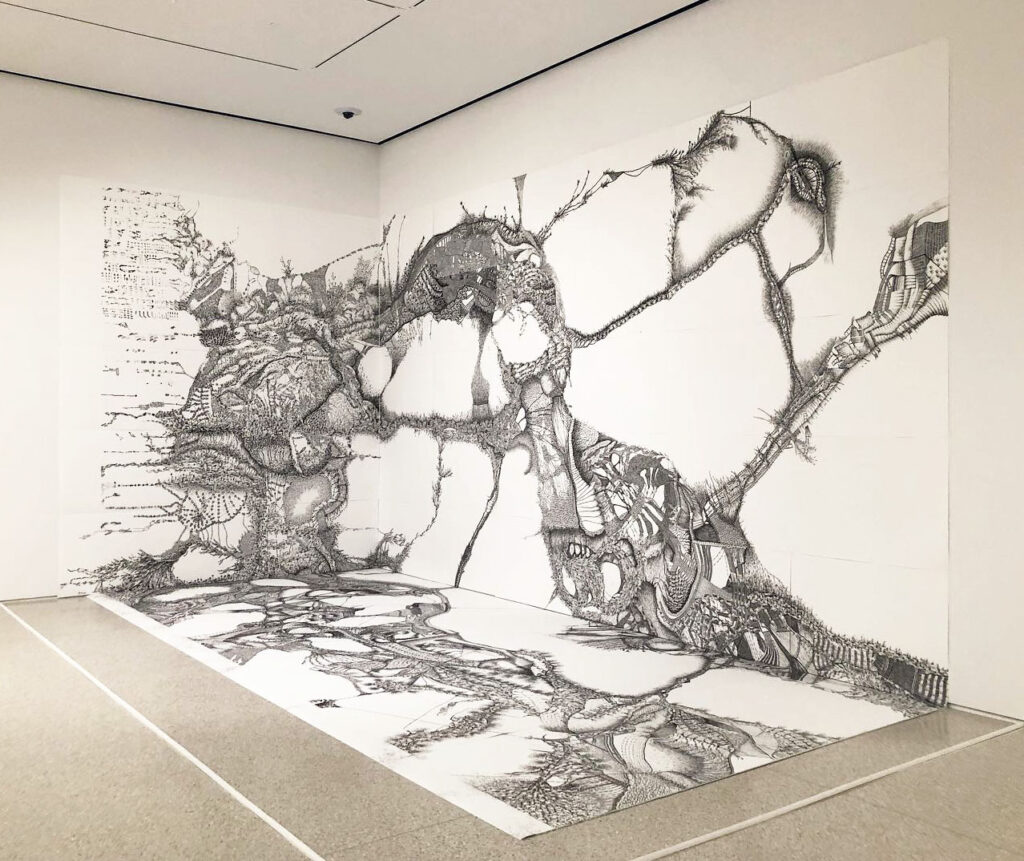

Brookhart Jonquil, “Groundless”, 2023, Mirrors, steel, acrylic paint, enamel paint

Brookhart Jonquil, “Groundless”, 2023, Mirrors, steel, acrylic paint, enamel paint (detail)

Brookhart Jonquil, “E)A)R)T)H)”, 2012, Mirrors, EPS, MDF, plaster, paint

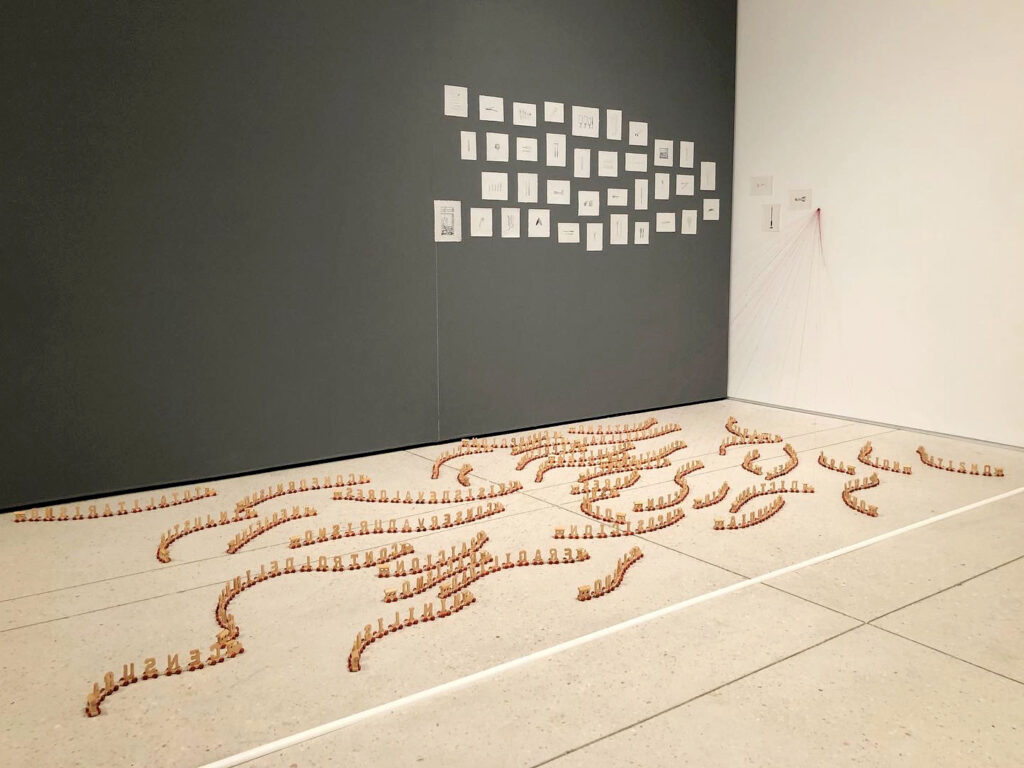

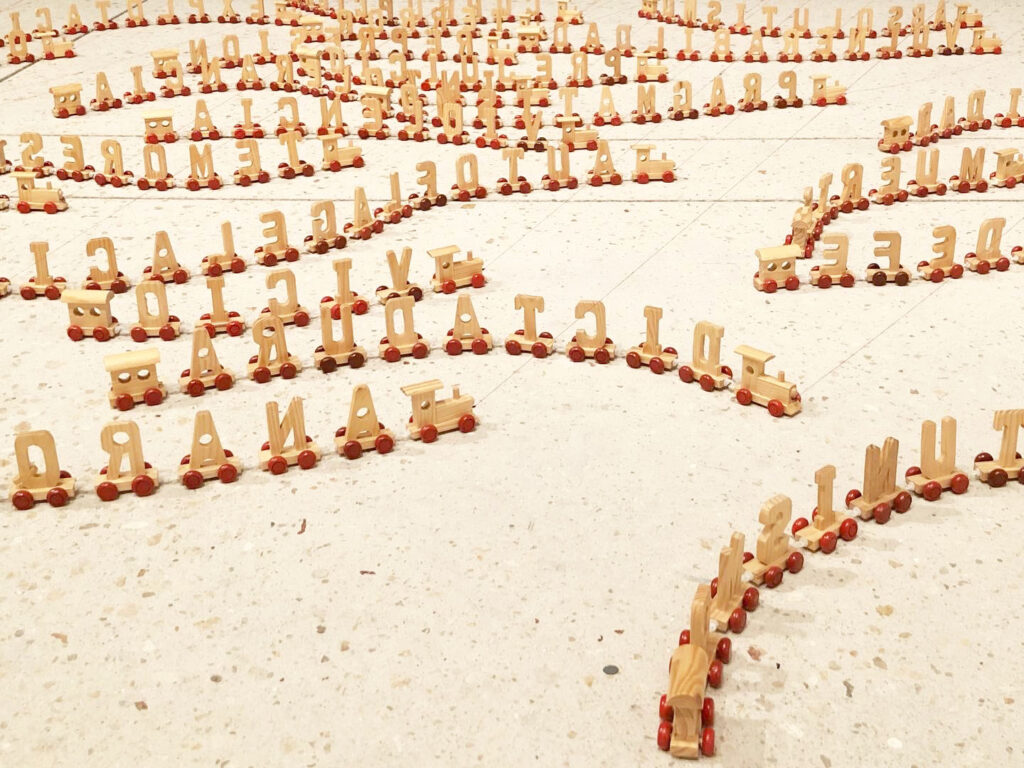

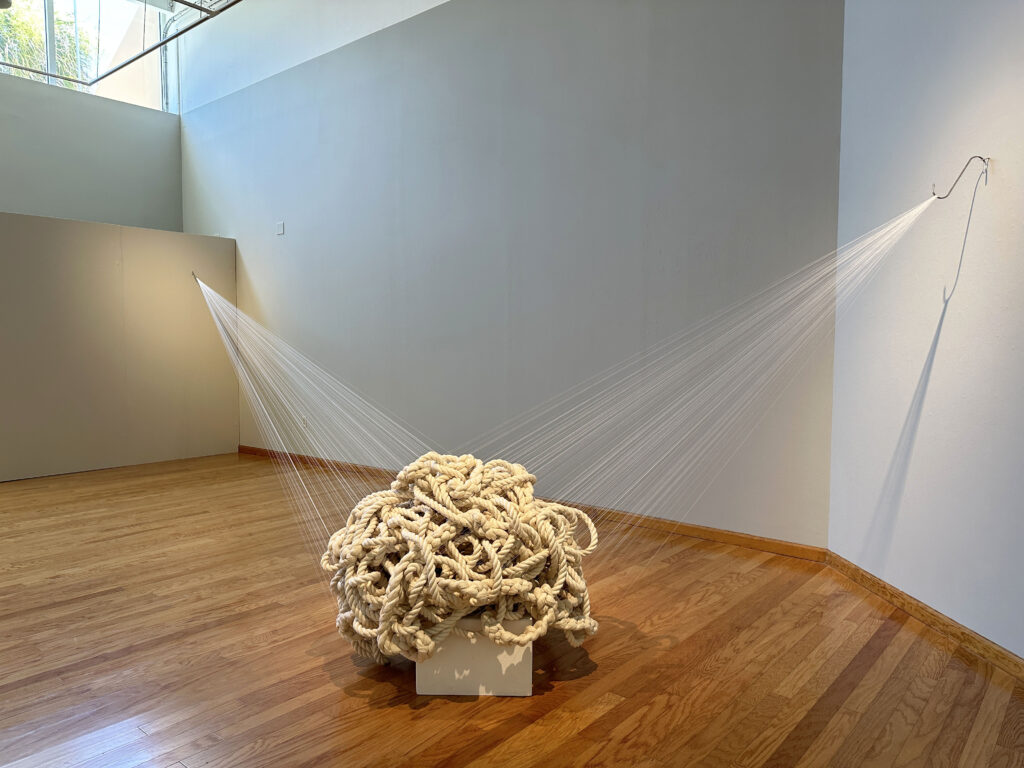

Brookhart Jonquil, “Multiplication Portal”, 2022, Plexiglass, water, powdercoated steel, plant cuttings, marine polymer sheet, pump system

Brookhart Jonquil, “Multiplication Portal”, 2022, Plexiglass, water, powdercoated steel, plant cuttings, marine polymer sheet, pump system

Brookhart Jonquil, “Multiplication Portal”, 2022, Plexiglass, water, powdercoated steel, plant cuttings, marine polymer sheet, pump system

Brookhart Jonquil, “Multiplication Portal”, 2022 (detail)

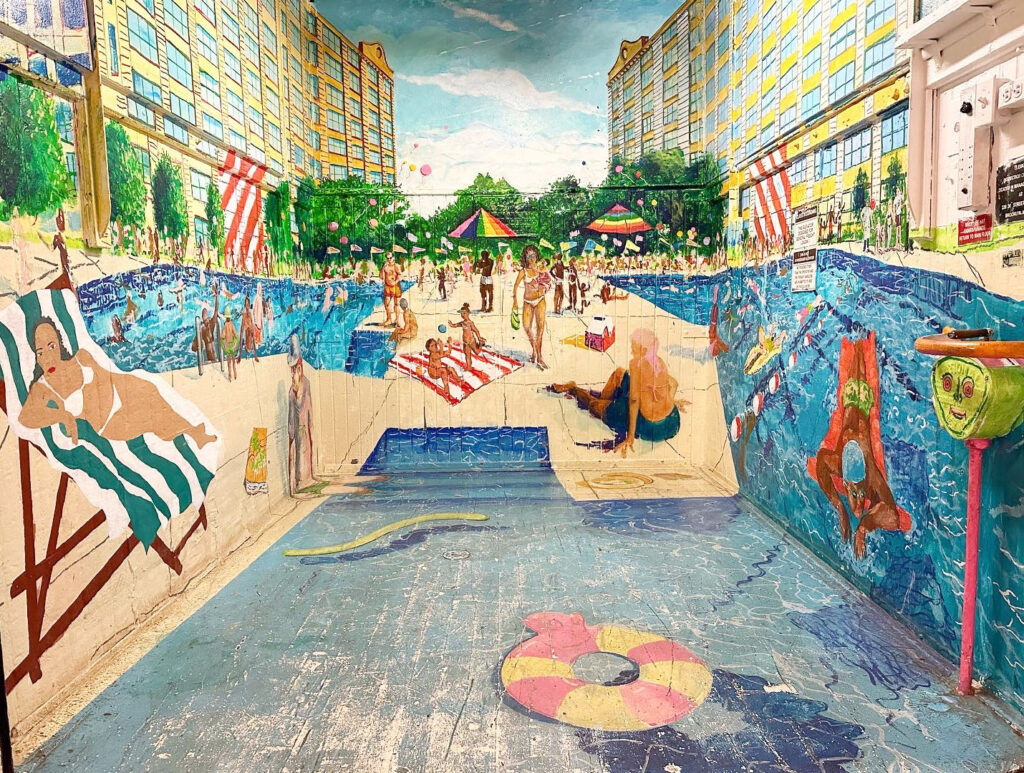

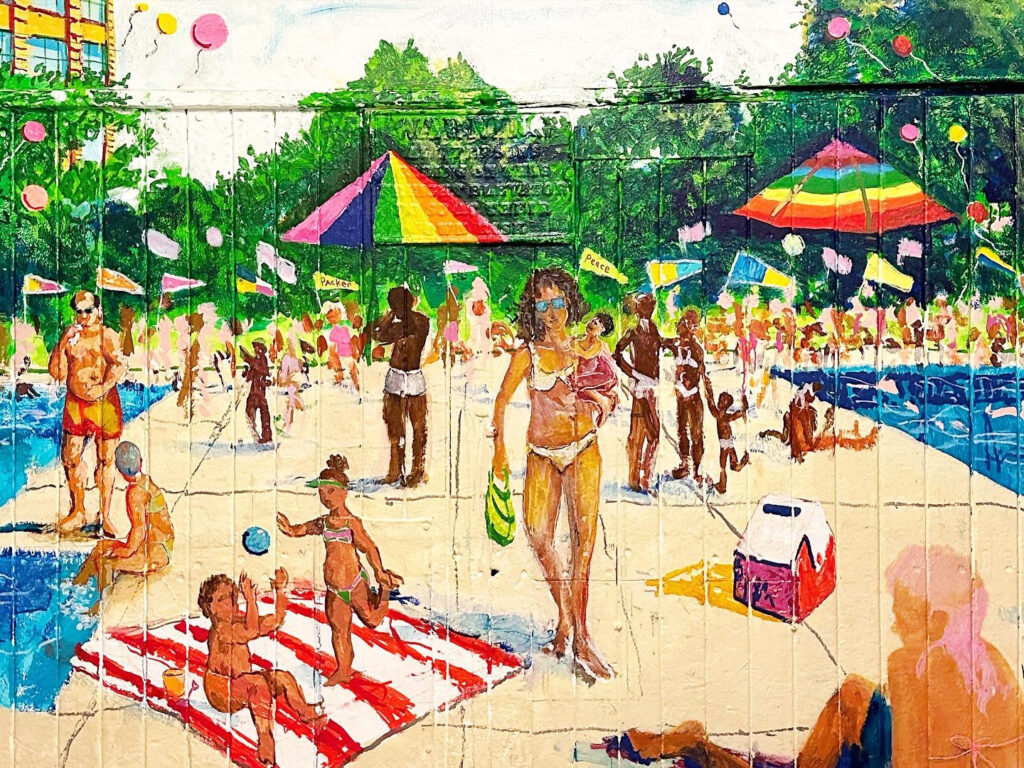

For The Nature of Art at the Museum of Fine Arts St. Petersburg, work from the exhibition is spread throughout different sections of the museum. In the Great Hall and Sculpture Garden are installations by Brookhart Jonquil.

From the museum about these works-

In this group of installations, Brookhart Jonquil creates art that engages physics, architecture, and ecology to explore the immaterial, shifting aspects of the natural world. His work reflects influences ranging from Minimalism to theories of utopia and perfection; it offers viewers new ways of seeing and a nuanced understanding of our place in the world. The works exhibited here and in the Sculpture Garden encompass over a decade of his career, illustrating how nature has always influenced his artistic practice.

Groundless is Jonquil’s most recent work, inspired by painting en plein air, the Impressionist practice of working outdoors. However, the artist has complicated this by incorporating mirrored surfaces that deny full control of his compositions. Jonquil notes, “Each stroke of paint multiplies unpredictably as I place it, while shifting colors and cloud-forms evade fixity.”

The floor-based sculpture E)A)R)T)H) uses five pieces of mirror glass to dissect an earthly sphere. Unlike Groundless, these mirrors reflect the Great Hall, foyer, and surrounding galleries, suggesting a macro-and micro-viewing of our planet. To further a sense of dislocation, Jonquil has inverted the colors typically associated with land and water: bodies of water are depicted in white, while land is blue.

Multiplication Portal-on view in the Sculpture Garden- is a participatory sculpture highlighting the care and responsibility involved in cultivating plants. Reminiscent of both a kaleidoscope and a beehive, it was inspired by chaos theory-also known as the butterfly effect, which is the idea that one tiny gesture can have colossal consequences within dynamic systems. Brookhart created Multiplication to fight environmental disillusionment. Can one individual impact the impending climate disaster? What is the point of separating paper and plastic? Does turning off the lights make a difference? Multiplication Portal serves as a reminder that our seemingly small actions have the potential for significant consequences.

In an upstairs gallery is the video installation, Blood, Sea by Janaina Tschäpe (seen below). The dreamy video takes you underwater to explore transformation through sea maiden myths.

Information on the installation from the museum-

Reminiscent of Voltaire’s Micromégas, Janaina Tschäpe’s fantastical scenes dissolve boundaries, seamlessly intertwining in an ever-flowing continuum of evolution and transformation in a grand opera that delves into themes of change, gender, and the construction of myth and history. The universe created by Tschäpe beckons one into a parallel world of ambiguous scale-indeterminate in both time and space. The spring-fed grotto provides the scenographic impetus for this grand production, a captivating fusion of a theme park nestled within a state park and bearing the distinction as one of Florida’s oldest roadside attractions. The sea maiden mythologies that inform Blood, Sea link endless stories from across time and space, as many cultures have some version of a water goddess. Millennia of previously unknown deep-sea creatures caught in fishermen’s nets spawned the mythic narratives that gave rise to these goddess/creature tales. From the Mami Wata spirits of West Africa to the water sprites of Irish lore, the trope of the sea maiden appears around the world and across time. Tschäpe’s primary connection is her namesake, the Orixa lemanja of Candomblé. This powerful water spirit is the Brazilian version of the many syncretic gestures born of the Yoruban Afro-Atlantic diaspora. But lemanja is merely one character in the global pantheon of the water goddess.

The split-tail mermaid motifs that adorn the exterior walls of centuries-old homes in the landlocked Swiss Alps are a testament to the enduring allure of the fish woman’s imagery. The split-tail represents the hybrid presence of both home and away, the perpetual dual identity of the émigré, and a curious cipher of Tschäpe’s experience living between the culturally antipodean points of Germany and Brazil. This existence places her between logic and magic, between Protestant rationalism and the mystical worldview of Candomblé, between the grey angst of northern Romanticism and the sensual elegance of the southern hemisphere. This ever-changing identity is evidenced clearly in Blood, Sea, where the video’s perspective perpetually shifts. At certain moments, the viewer finds themselves aboard a ship, assuming the role of a scientist discovering a previously unknown life form. In other instances, we have the privilege of swirling amidst the creatures, becoming one with them.

This exhibition closes on 4/14/24.