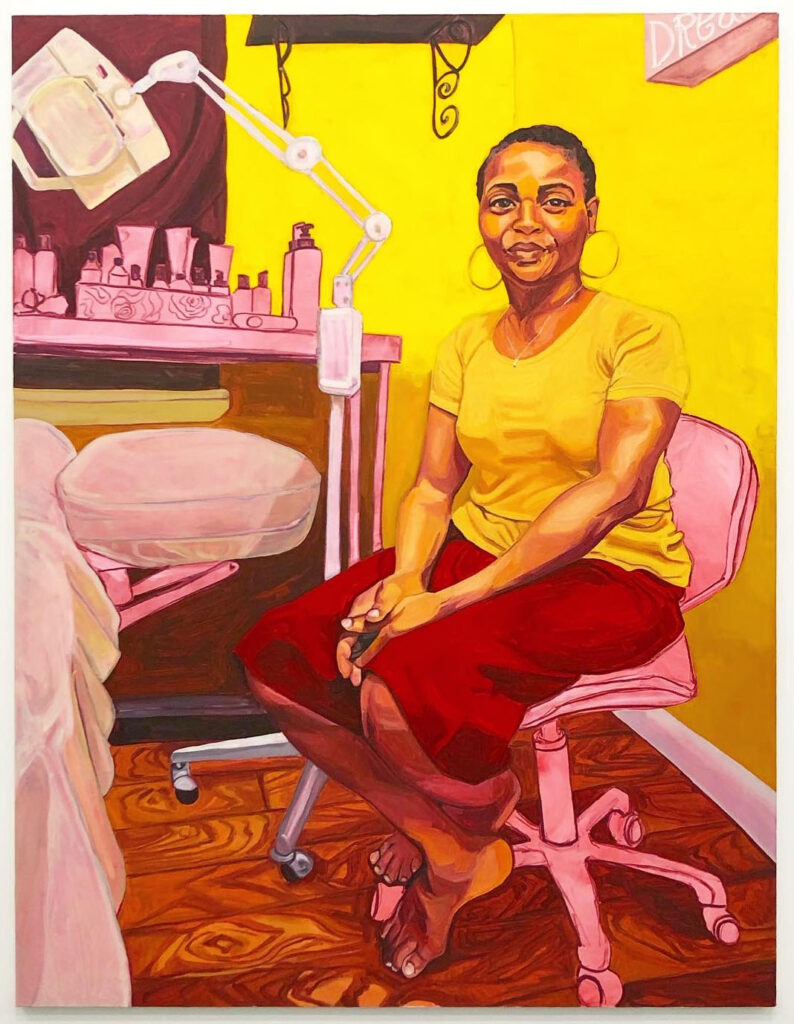

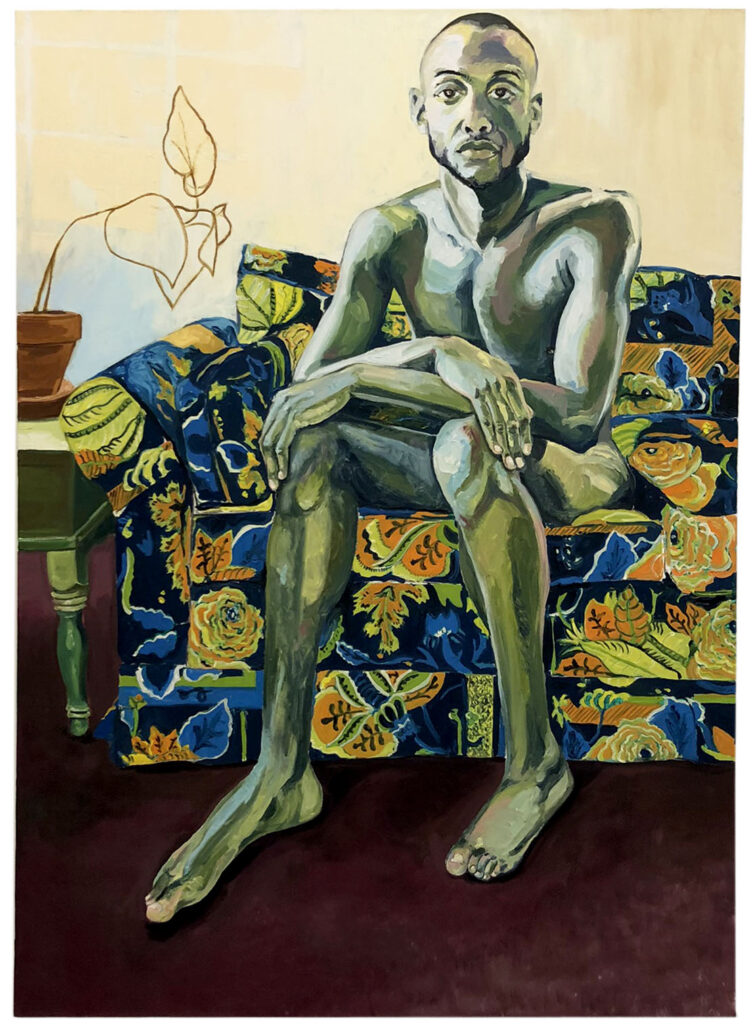

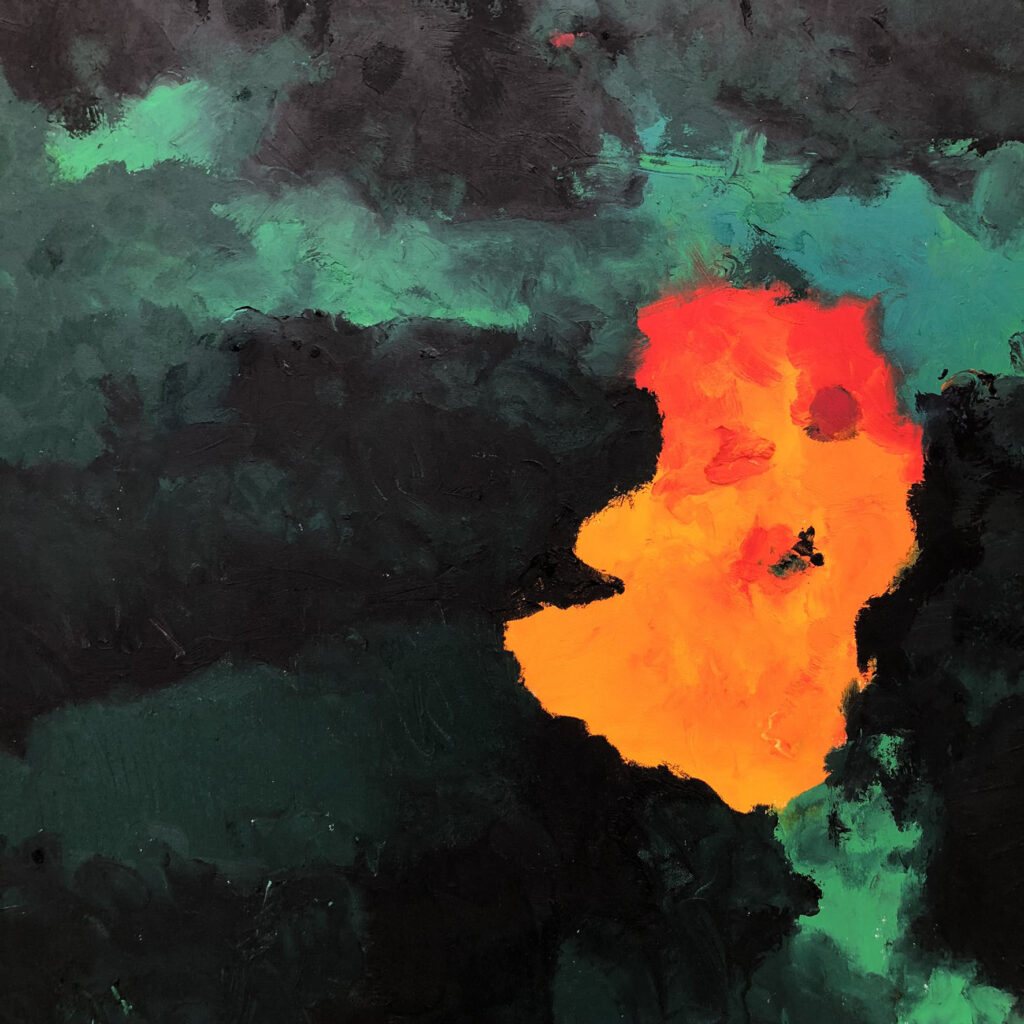

Ted Gahl “Purgatory (2)”, 2022

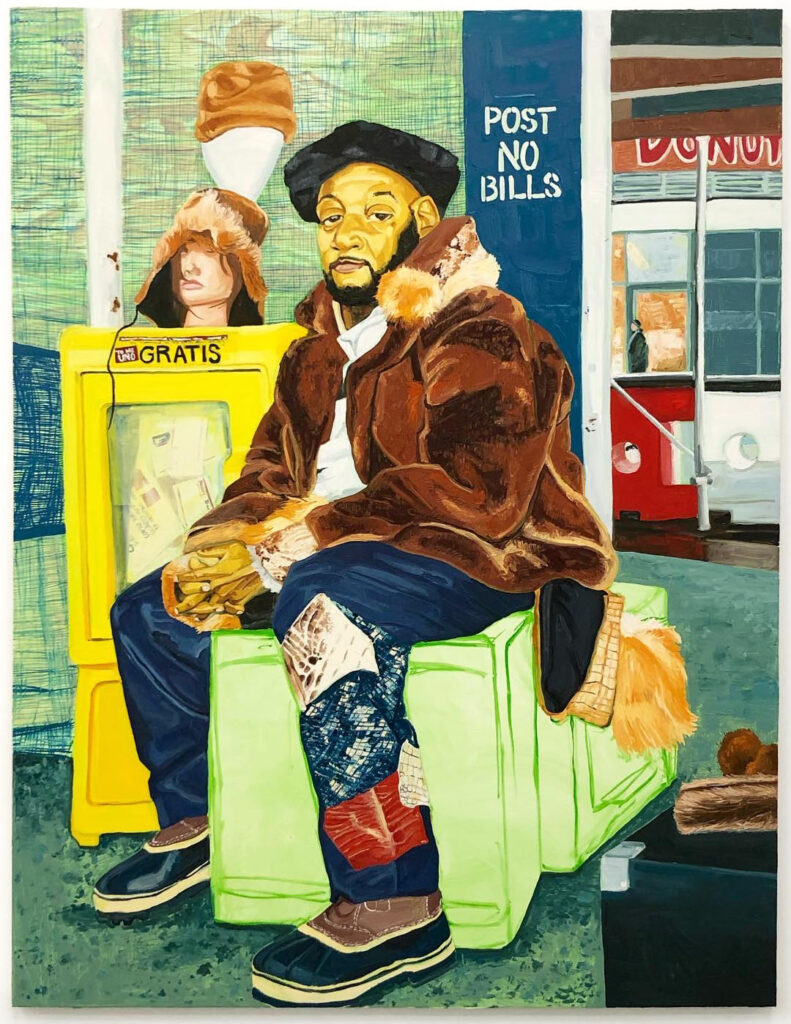

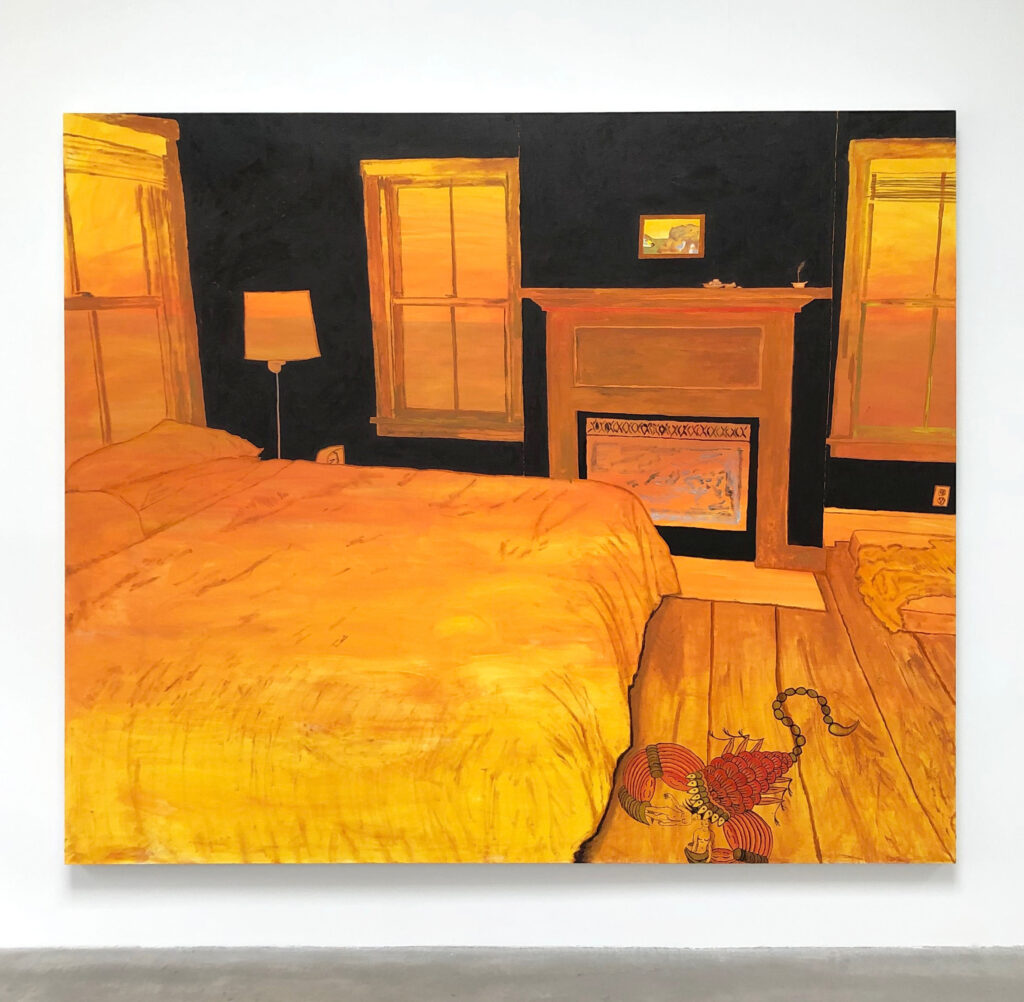

Ted Gahl “Woman Putting on Jacket”, 2022

Ted Gahl’s paintings for Le Goon at Harkawik Gallery draw you in the more you look at them, revealing layers of imagery.

From the gallery’s press release-

Building on imagery he developed in “Stories from the City, Stories from the Sea,” here he delves further into an ocean of muted memories and historical associations that are legible only as hazy apparitions. Gahl charts a course through an emotionally charged landscape: a trench where isolation and connection embrace, where melancholic figures strain to make contact with an ineffability beyond the border of the canvas. Through a dialogue between small, mid-size, and large-scale paintings on unstretched canvas, Gahl implores us to look under the surface, offering attentive viewers the gift of conjuring new meanings over time.

The frames on Gahl’s smaller paintings are composed of chopped paint stirrers, a nod to the artist’s youth spent painting houses and lattice framing techniques of the past, as well as an interest in blending high and low culture. He juxtaposes smaller figurative works with gargantuan 8-feet tall paintings that cascade down unstretched canvas, rooted in abstraction inspired by landscape. These large paintings are intuitive, with one movement or color influencing the next, allowing the artist the physical space to deepen his investigation of consciousness. He calls these works “tarps,” a nod to the cloths thrown down to catch errant paint drips. Here, he deepens his ethical engagement with the many modalities of paint and creative labor.

The artist employs figuration as a vehicle to explore abstraction, seamlessly gliding between the two methods. Figures are adorned in coats that serve as portals into another dimension, brimming with thin layers of muddy greens, sky blues, and merigold oranges that feel plucked out of a Post-Impressionist painting. Within Gahl’s controlled confines of abstraction, the world enlarges, revealing traces of the night sky, throngs of people, fish in a stream.

Gahl’s work is intensely cinematic, as if projected onto a screen or trapped inside an unraveled roll of film. Several scenes unfold within a single painting, allowing a multitude of emotion to erupt. Fleeting moments of tension abound. Two nude women emerge from a body of water reminiscent of a Georges Seurat or Milton Avery landscape, but their togetherness is fractured by a hulking tower of darkly-hued abstraction. A translucent trio bathing in a deep Rothko red exudes a biblical aura; an outline of an angelic body reaches towards the top of the canvas. Gahl’s airy yet deft brushstrokes feel like wading into a pond, while a ghostlike figure dissolves into the landscape, as if imprisoned in the sparse solitude of a Norbert Schwontkowski painting. The artist plays with the horizon, causing us to question if the shadowy form is sinking into water or simply lying in the grass. Are we above or below ground? Is this death or relaxation? Are they the same thing?

At the heart of Le Goon lives a yearning for connection. Mortality cannot help but leak through the canvases and become personified. Gahl’s work invites us towards intimacy, towards deeper questioning. The answers emerge from the water and evaporate towards the heavens before we can touch them, leaving us only with the feeling of the mist kissing our skin.

—Lauren Gagnon

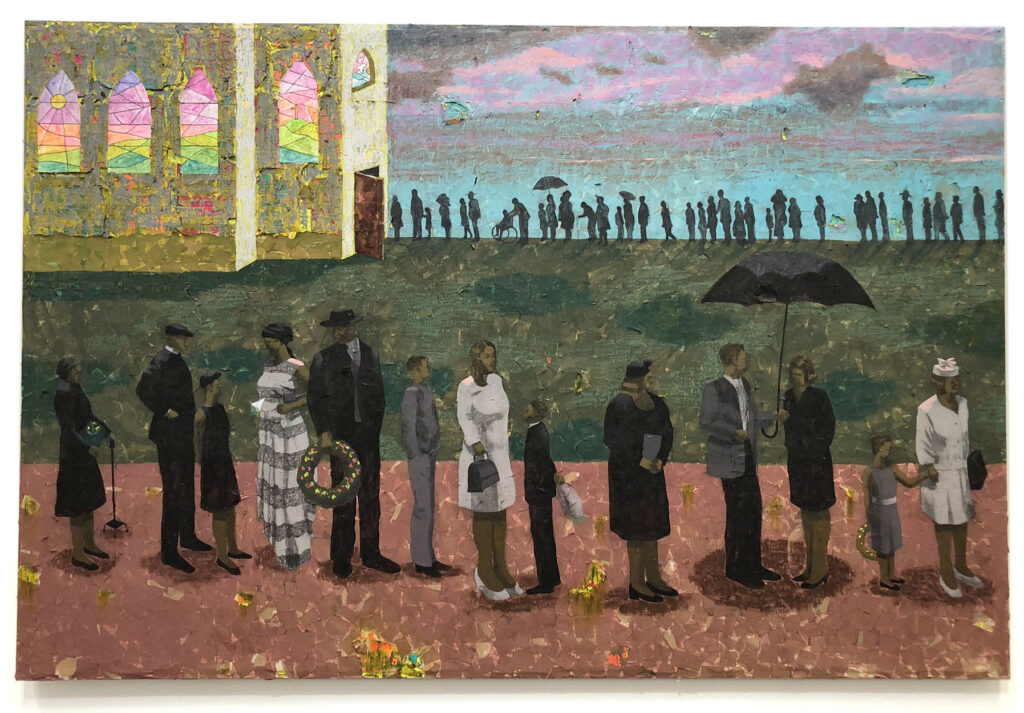

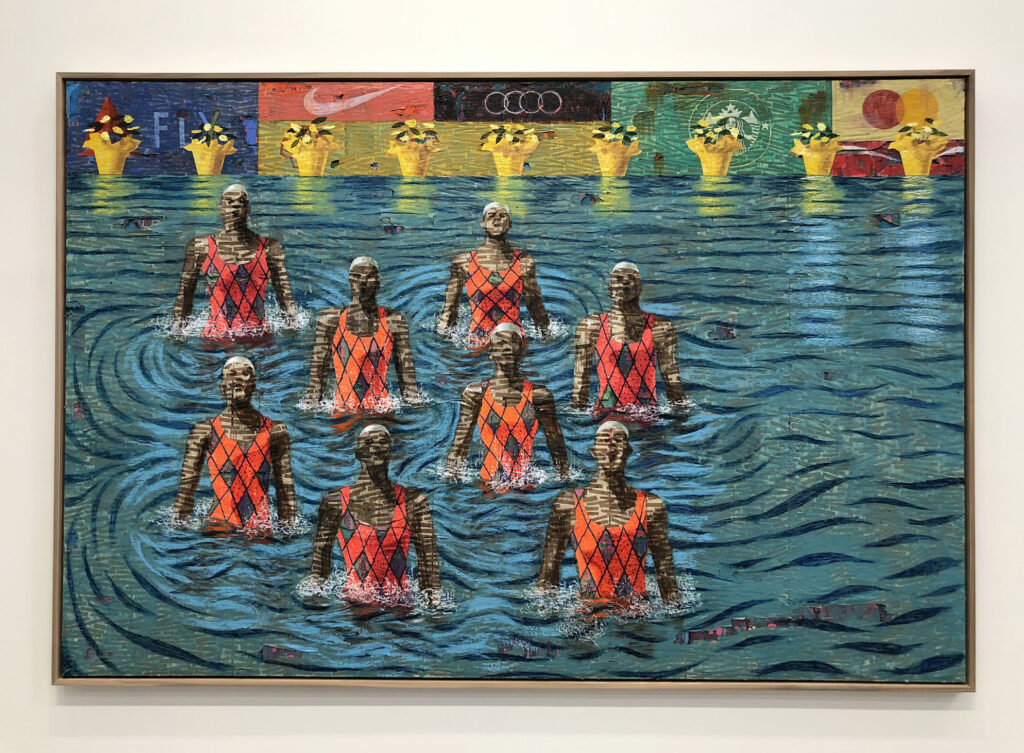

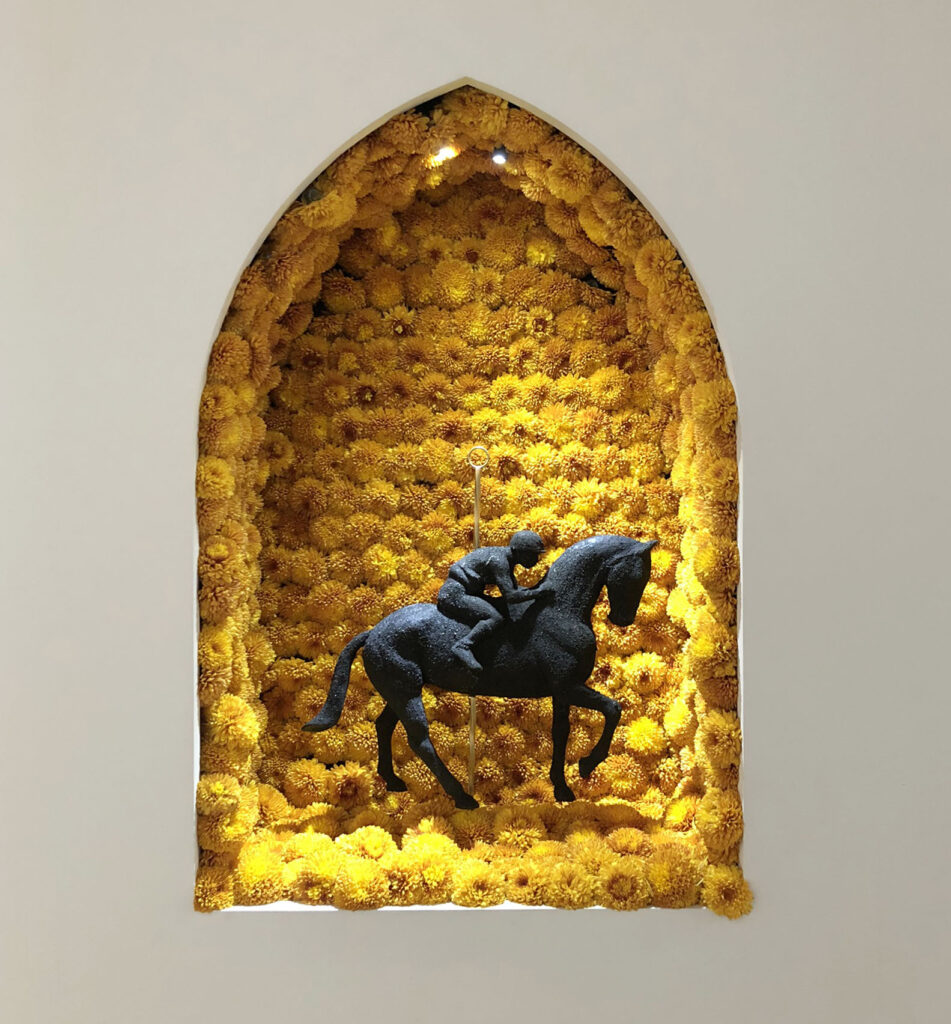

Also at Harkawik are Eli Hill’s recent paintings for Some Days I Taste The World, a series of works that use the natural world to approach topics of identity.

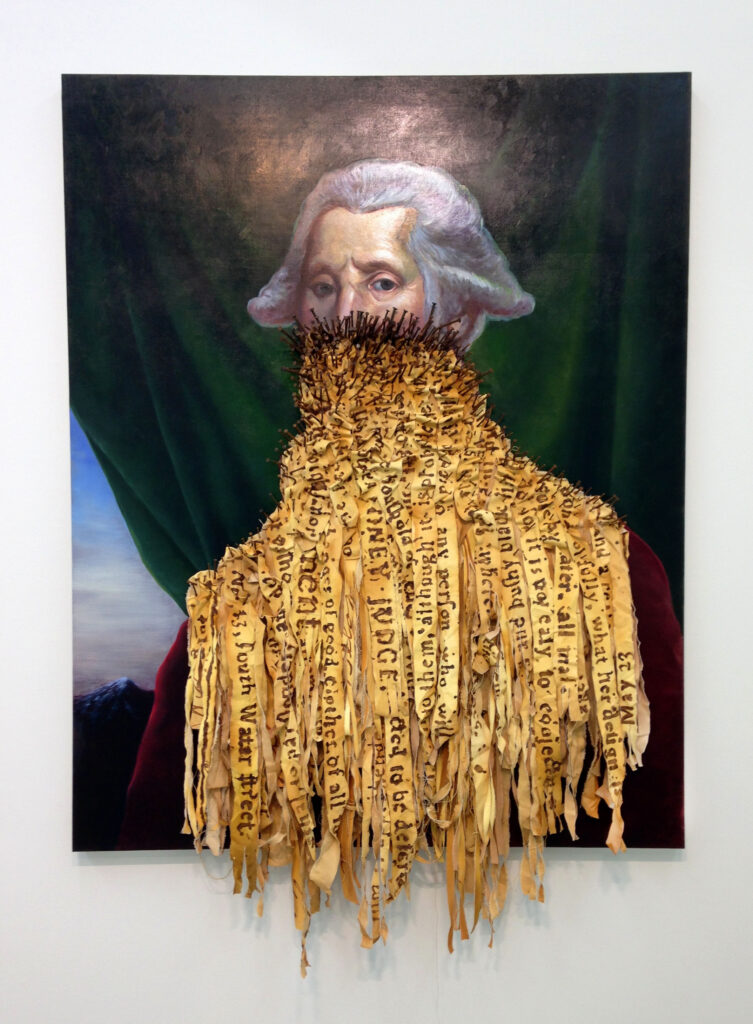

Eli Hill “Wineberry Sight”, 2022

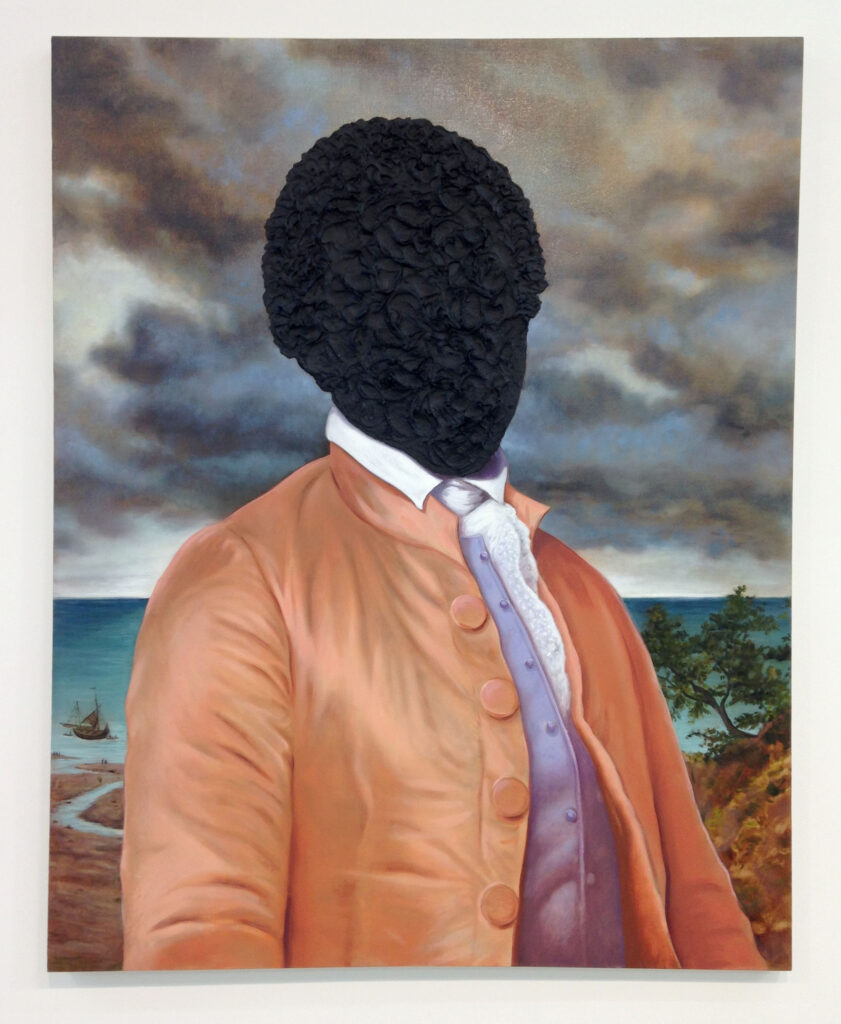

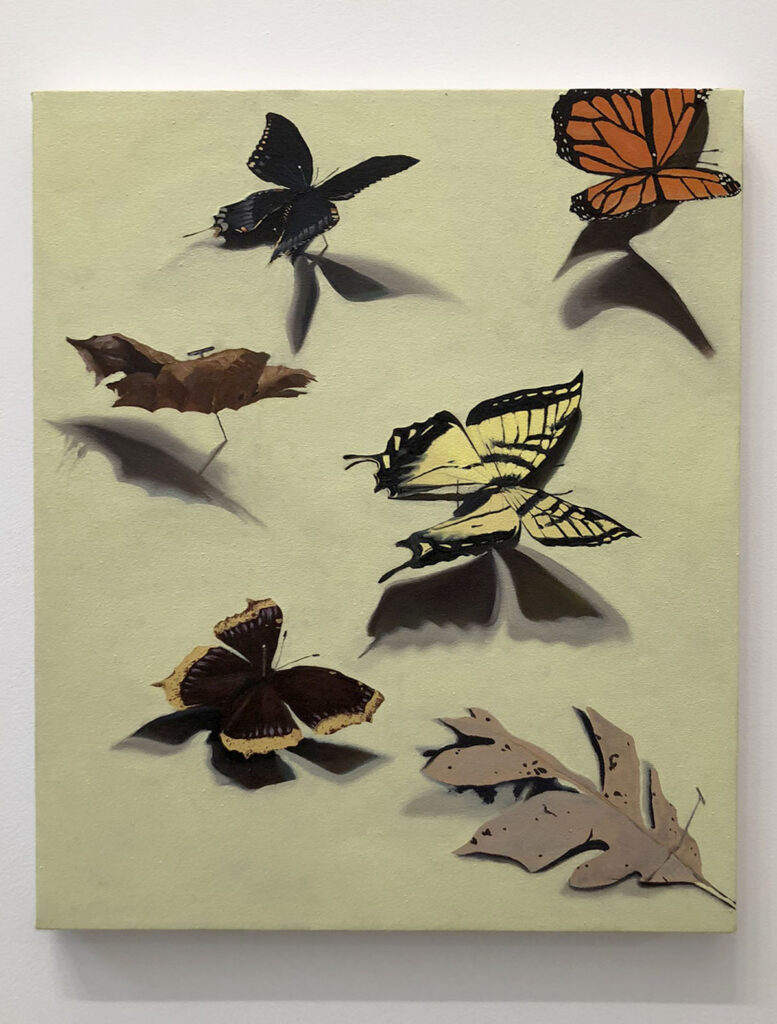

Eli Hill “Decidousness”, 2022

From the gallery’s press release-

Comprised of nine mid-size works, Some Days evidences Hill’s fascination with the way in which humans order and classify the natural world. His paintings speak to the problematics of anthropology, the subversion of the naturalist’s impulse to categorize, and the painter’s age-old communion with nature. Hill proposes a fascinating configuration of personal, political, and scientific concerns and draws parallels between the transgender body and planet Earth. Hill’s canvases merge figurative and landscape traditions, calling attention to the ways in which bodies—celestial, earthly or otherwise—are routinely subject to binaries, alienation, hierarchy and the struggle for survival and self-actualization.

The majority of the exhibition’s paintings are derived from the artist’s long distance runs and environmental work in the leafy Queens oasis of Forest Park. Here, we bid farewell to the gray grit of the city and emerge into a landscape that is simultaneously natural and hallucinogenic. Verdant greens and earthy browns mingle with pale lavenders and silvery blues. The umber shadows of trees streak the soil, basking in the blood orange glow of an artificial sunset. Fluid brushstrokes waterfall down the canvases. Hill’s paintings of the natural world are borderline devotional; he is imploring us to worship the beauty and drama of nature in its fullness. Not unlike the still-lifes of Rachel Ruysch, insects creep out and leaves decay and decompose back into the earth. Split depicts a tree the artist passes by, an image so striking you can almost hear the sound of bark cracking. The branches are split in half and upheld by the flora around it. Community, mortality, and the life cycle are omnipresent.

While some of Hill’s paintings engage traditional modes of depiction, others shift between recognizable and unrecognizable subjects. In Wineberry Sight, the invasive wineberry shrub masquerades itself as a raspberry bush to ensure survival. But are we peering through an eye of vines or veins? By creating images that refuse us easy associations, he provides an opportunity to find pleasure in images we cannot name or categorize. Under every branch we find trickery, performance, preservation. The notion of the “invasive species” itself calls attention to the ideological structures at play in our understanding of what’s “original,” “natural;” what has a right to proliferate and thrive.

The exhibition title is a line from a CA Conrad poem, as well as an homage to the influence of the poet’s writing and spiritual practice in Hill’s work. Revolutionary care permeates Hill’s depiction of the figure; whether his own body, a tree, or a friend, he actively opposes mining, objectifying, or exploiting his subjects. In The Artist as a Naturalist, a self-portrait is accompanied by two paintings within a painting of colorful moths. The work demands time and effort, as awkward cropping abstracts the body, consequently resisting commodification and denying easy consumption of the work from a historically cisgender gaze. Like German-Swedish figurative painter Lotte Laserstein’s Portrait With a Cat, Hill consolidates naturalistic observation with a figure that gazes back at the audience. The painting itself possesses a sort of agency, as multiple pairs of eyes appear, aware we are observing them, and throwing into uncertainty the subject of the examination; them, us, something else?

Some Days I Taste the World is like walking through a Ralph Waldo Emerson essay, where beauty takes on a cosmic quality that transcends the experience of individuals. Hill offers us a fascinating configuration of previously known quantities, suggesting a natural place for things like radical queer joy. Through a dense canopy sunlight streams through, lighting up our faces.