Sarah Meyohas, “Interference #19”, 2023, Holograms, mirrored black glass, aluminum

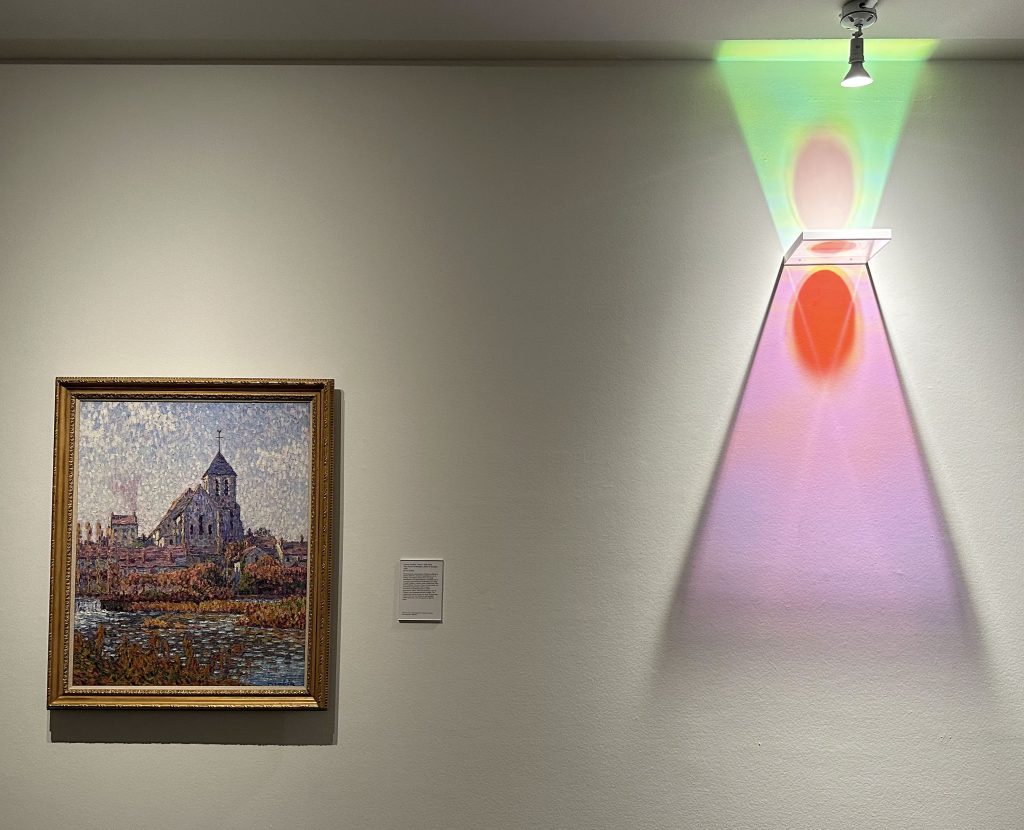

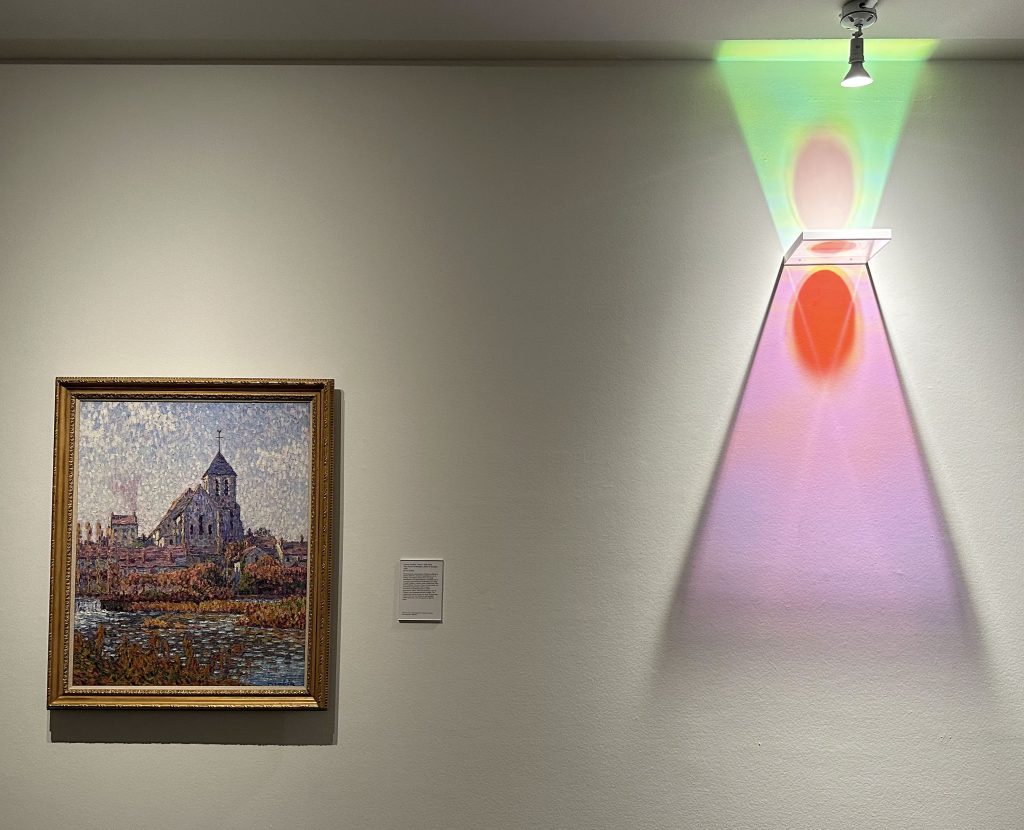

Francis Picabia “The Church of Montigny, Effect of Sunlight” 1908, Oil on canvas (left); Christian Sampson “Projection Painting”, 2023, Acrylic and films with LED light; and Claude Monet “The Houses of Parliament, Effect of Fog, London” 1904, Oil on canvas (right)

The Nature of Art exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts St. Petersburg merges art from the museum’s collection with loaned works to explore- “art’s crucial role in our evolving quest to understand our relationship with nature and our place in the cosmos”.

One of the benefits of an encyclopedic museum is that visitors have the opportunity to experience art throughout history, and to revisit works that resonate with them. For the section titled Artist as Curator, Sarah Meyohas and Christian Sampson chose pieces from the museum’s collection to pair with their own work.

From the museum-

At first glance, perhaps, these may seem like unusual combinations, but upon deeper contemplation, their selections reveal complementary artistic intents. For instance, Meyohas and Georgia O’Keeffe share an interest in close looking, particularly in finding new ways to examine underappreciated aspects of the natural world. Sampson, influenced by the California Light and Space Movement, is interested in current scholarship that suggests the hazy fog found in Claude Monet’s work is an early depiction of air pollution, offering an entirely new perspective on the artist’s representations of light.

Sampson also created the four-part installation, Tempus volat, hora fugit, on view until 2025 at the museum.

Below are some of the works from additional sections of the exhibition.

Postcommodity, “kinaypikowiyâs”, 2021, Four 30.5-metre industrial debris booms

Postcommodity, “kinaypikowiyâs”, 2021, Four 30.5-metre industrial debris booms

Postcommodity is an interdisciplinary art collective comprised of Cristóbal Martínez (Genizaro, Manito, Xicano), and Kade L. Twist (Cherokee).

About Postcommodity’s work, kinaypikowiyâs, (seen above) from the museum-

This work is composed of debris booms, used to catch and hold environmental contaminants such as garbage, oil, and chemicals. The colors of the booms correspond to different types of threats— red (flammable), yellow (radioactive), blue (dangerous), and white (poisonous)-in the labeling system for hazardous materials. To indigenous peoples, these are shared medicine colors that carry knowledge, purpose and meaning throughout the Western Hemisphere. Suspended like hung meat, the booms represent a snake that has been chopped into four parts. Each part represents an area of the colonial map of the Western Hemisphere: South America, Central America, North America, and all of the surrounding islands. The title, kinaypikowiyâs, is a Plains Cree word, meaning snake meat. Divided by borders, Postcommodity asserts that all people living in the Americas are riding on the back of this snake.

James Casebere, “Red/Orange Solo Pavilion”, and “Orange Guesthouse”, 2018, Archival pigment print mounted to Dibond

James Casebere, “Landscape with Houses (Dutchess County, NY), 2009, Archival pigment print mounted to Dibond

James Casebere creates architecturally based models for the large scale photographs seen above.

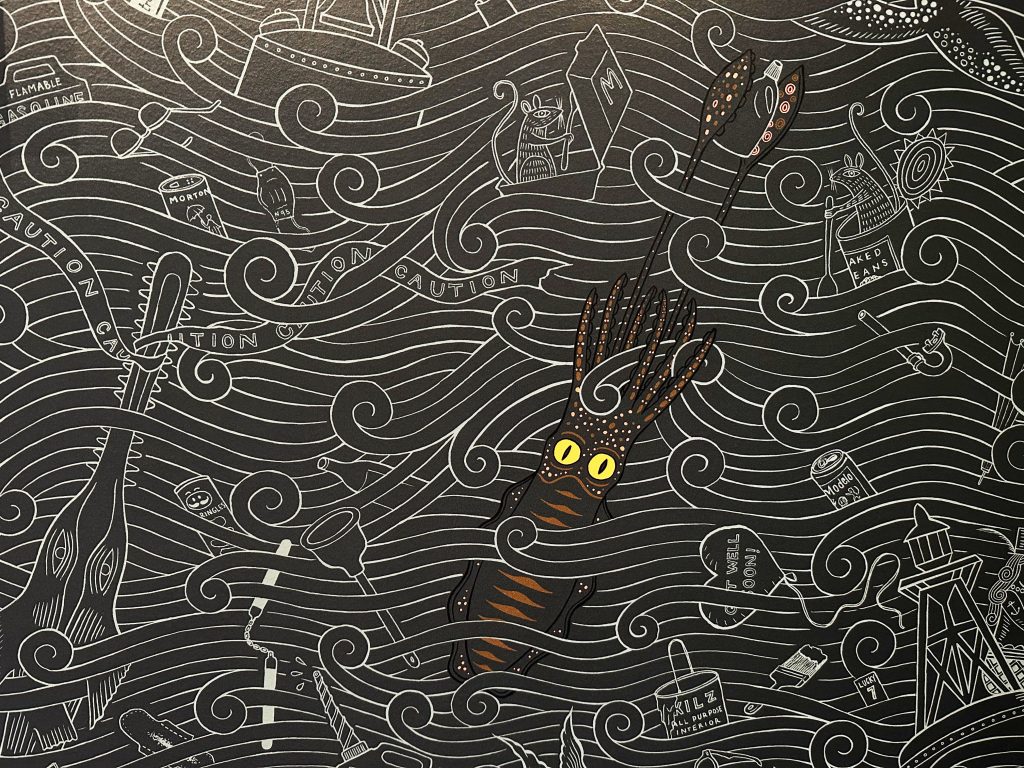

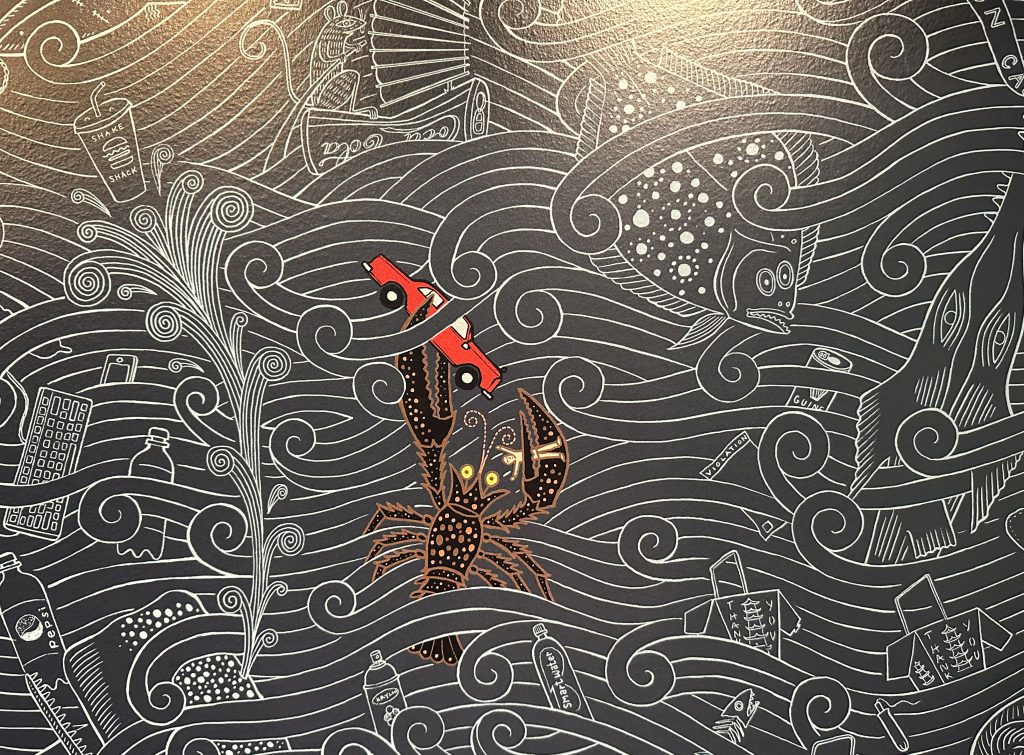

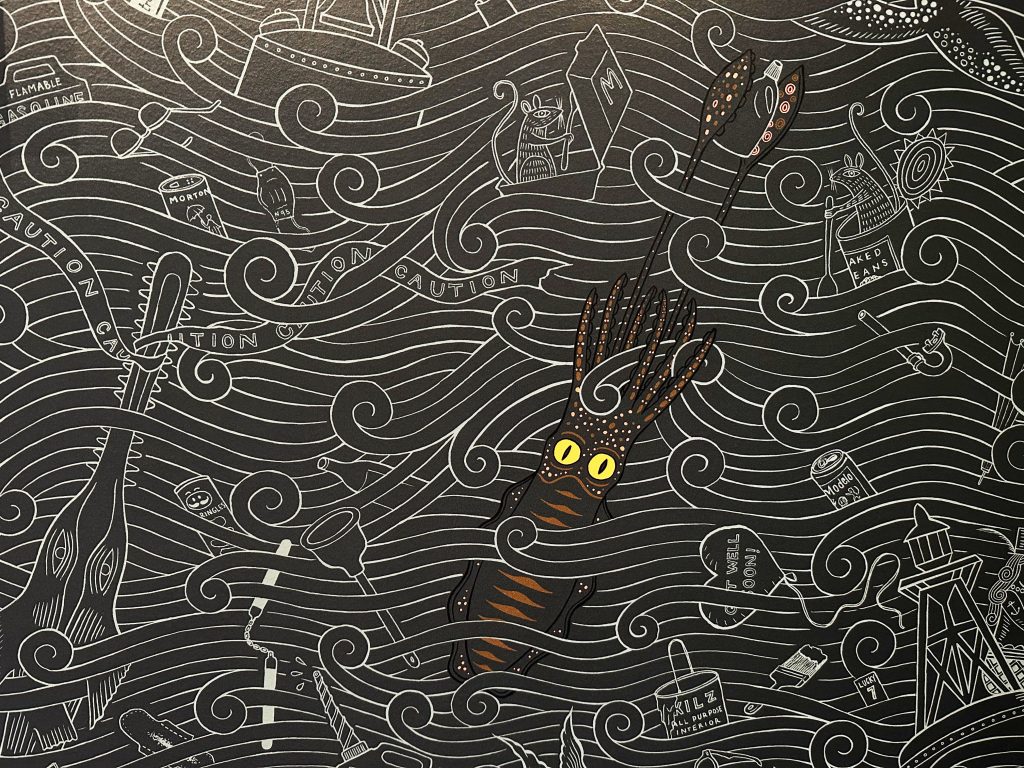

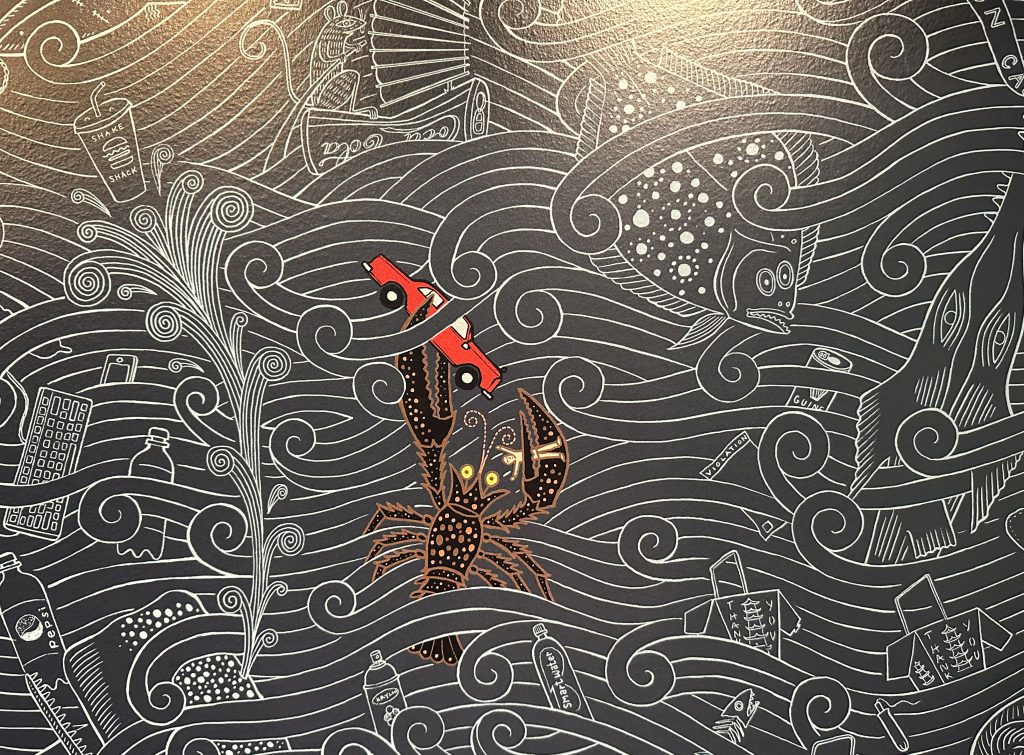

Reclaimed ocean plastic sculptures and “Tidal Fool” wallpaper by Duke Riley

Duke Riley custom wallpaper, Tidal Fool, detail

Duke Riley custom wallpaper, Tidal Fool, detail

Duke Riley’s work, which was previously shown at Brooklyn Museum, addresses issues of environmental pollution by using discarded plastics found in the ocean and other waterways to create new work inspired by the past. You can hear him discuss his work in this video.

From the museum-

Inspired by the maritime museum displays he saw while a child growing up in New England, Riley’s scrimshaw series is a cutting observation of capitalist economies-historic and today-that endanger sea life. The sculptures were created for the fictional Poly S. Tyrene Memorial Maritime Museum, and are contemporary versions of sailors’ scrimshaw, or delicately ink-etched whale teeth and bone. Riley first thought about using plastic as an ode to scrimshaw when he saw what he thought was a whale bone washed up on the beach in Rhode Island; it turned out to be the white handle of a deck brush. Riley regularly removes trash from beaches and waterways, and often uses this refuse in his work.

Riley collaborated with Brooklyn-based Flavor Paper to create these two custom wallpapers for his solo exhibition DEATH TO THE LIVING, Long Live Trash at the Brooklyn Museum. Tidal Fool exhibits Riley’s trademark humor in the face of devastating water pollution; notice the Colt 45-guzzling mermaid. Wall Bait vibrantly references Riley’s meticulous fishing lures, which he crafts from refuse found in the waters around New York City.

Daniel Lind-Ramos,”Centinelas de la luna nueva (Sentinels of the New Moon)”, 2022-2023, Mixed media

Daniel Lind-Ramos,”Centinelas de la luna nueva (Sentinels of the New Moon)”, 2022-2023, Mixed media

Daniel Lind-Ramos also uses a variety of recycled objects to create his sculptures.

From the museum about this work-

In Centinelas de la luna nueva, he evokes the elders of the mangroves, spiritual beings who watch over and ensure the health of this essential coastal tree. Mangroves are the basis for a complex ecosystem that shelters sea life and serves as the first line of defense in the tropical storms that batter the sub-tropics—including Florida.

Lind-Ramos’s practice reflects the vibrant culture of his native Loíza, Puerto Rico, by honoring local agriculture, fishing, cooking, and masquerade. His sculptures also evoke Hurricane Maria (2017), the COVID-19 pandemic, and ongoing environmental degradation. Lind-Ramos is committed to the survival and sustenance of Afro-Taíno traditions and people of the Puerto Rican archipelago. However, his art engages the global community through shared emotions, parallel histories, and the commonality of human experience.

The next post will discuss two other artists in the exhibition, Brookhart Jonquil and Janaina Tschäpe.